-

An Apology Primer

This time of year can seem like a replay of familiar words: apology, pardon, forgive. But, what does it all mean, how does it work, and which comes before which?

Last Saturday night marked the beginning of the week before the Jewish New Year, of Rosh HaShana. The name of the special late night service is Selichot, which means ‘pardons’ in Hebrew. This is one way the Jewish New Year differs from a secular new year: we accept that we have made errors, reflect on how we may have missed the mark in the past year, apologize, and ask for forgiveness. We do this so that we can move forward with newer, better, attitudes and behaviours. The word for this turning around from a problem behaviour to a new, improved one is, Teshuva, which literally means, turning around.

But, really, who are we apologizing to, and what is most important: the apology or forgiveness or the resolve to change? and for whom is our apology or forgiveness meant?

These are questions behind centuries-old beliefs and practices in Judaism; are they still relevant to today? The answer is a resounding, Yes!

Here is an modern example of how apology, forgiveness, and change are interrelated:

A friend has run a monthly group program for a non-profit organization for many years. Unfortunately, the office administrators, every month in all those years except for 2 or 3 of them, advertise the program incorrectly to the hundreds of it members on the mailing list. That is, the date or time or is wrong, or it just doesn’t get advertised. The errors are different every month. Every month, my friend has to ask the office to correct the problem(s). And, every month the office administrator apologizes, only to make errors again the next month. Conversations initiated by my friend to come to a better outcome with the office provide no change, and the errors continue to go out.

This reminds me of the ‘Peanuts’ cartoons, in which Lucy perpetually tricks Charlie Brown into believing she will hold the football in place for him when he goes to kick it. I hate to think of adults behaving the way Lucy does, or for that matter, as Charlie Brown does. This will be an endless, shameful, dynamic unless one of them resolves to change, or to turn around, in Teshuva, and be released from this endless cycle of victim and perpetrator.

Teshuva is really not as complicated or difficult as we might think. Knowing the territory, having a map, makes it more attainable. We first have to acknowledge that there is a problem. In the case of my friend, this was pointed out to the office, and Charlie Brown also discusses his concerns with Lucy. The next step would be for the office administrator or Lucy to recognize or care about how their behaviour has caused hurt or harm to someone else. An apology may go out, and even words saying it won’t happen again, or even what they will do differently next time: but the real apology happens when the hurtful behaviour stops.

Sadly, Lucy keeps tricking Charlie Brown, and the office keeps tricking my friend.

So, what do we do when the behaviour continues? And, do we forgive someone simply because they said, ‘I’m Sorry’, but their behaviour did not change? There is more to information about this in our road map.

I have bookmarked some useful readings with a very modern understanding of the importance of making real inner change as an integral part of apologizing:

- At The Well: Sorry, Not Sorry: The Real Path to an Apology By Hanna Perlberger

- The Jewish Woman: Saying ‘I’m Sorry,’ and Meaning It By Samantha Barnett

- The Times of Israel: Don’t just casually say sorry, focus on changing in the future Eytan Saenger

It is important also to note that apologies may not come your way, even if you believe they are due, and that is okay.

The other party may not understand how to apologize, or feel uncomfortable, or embarrassed, or not know how, or have other barriers to owning their error. Or, it maybe it is that no error was made at their end. Whatever the reason, it can be a very long time to wait for an apology that never comes, and a long time to be on hold in a queue that is now taking up your time and attention. This is where forgiveness may help you to move on.

Moving to forgiveness does not require an apology. There may be a myriad of reasons why you didn’t receive your apology, and thinking of what possibilities there are might be useful. It is also important to look for a change in behaviour instead of the words of apology.

A friend once told me that the only ones who like to be changed are babies.

It’s true. You can’t expect to change others, but you can change yourself. Think of how football might be for Charlie Brown if he asks Lucy do something other than hold the football for him, or if Lucy apologizes and then honestly and consistently holds the ball properly for him to kick.

Notice yourself. What can you do to change so that if put in the same situation again, you have a plan that allows you to replace a cycle of errors or harm with success. Reflecting on what went wrong and how you can change, can release you from burdens you no longer wish to have.

Think about what you might need to change or let go of from this past year. If appropriate, apologize to yourself or to the other person. Then, think about what you would do if the same situation arose again: how would you handle it next time? and then employ the new pattern.

Know that forgiveness of self and others comes when change happens for the better: for growth, for health, and to make the world a better place for everyone.

Shana Tova, A Good New Year…Susan

-

Work on What Has Been Spoiled

Originally published on 5 October, 2022

As the waters of the COVID-19 pandemic’s tsunami of disruption recede, our world of experiences and expectations have changed, too. What had formerly been familiar now has an uncanny cast to it; favourite places for entertainment, work, travel, recreation, places of worship, and healthcare institutions look and operate unlike they ever used to, even as restrictions to access are lifted.

As the waters of the COVID-19 pandemic’s tsunami of disruption recede, our world of experiences and expectations have changed, too. What had formerly been familiar now has an uncanny cast to it; favourite places for entertainment, work, travel, recreation, places of worship, and healthcare institutions look and operate unlike they ever used to, even as restrictions to access are lifted.So many of us sat through this pandemic, chafing at the bit to go back to having things the old way, the familiar way: the way we, and our ancestors before us, made them. But, these things are forever changed, in our memories, in our minds, in our emergence back into them post-pandemic.

Rather than trying to fit all the pieces back in, as they once were, imagine instead that we had been afloat in an Ark, such as that of the Biblical Noach. We and all the living beings gathered into it, have been weathering a Great Flood. In Noach’s Ark, do you think that the passengers all imagined, in their human and non-human minds, that things would be just the same once the rain stopped?

Now, imagine yourself after a similar pandemic great flood, jostled and perhaps cast afloat: and the waves have relaxed. Deposited by a gentle surf, face down upon a wet sand of some strange beach; exhausted, grateful for the solid land, confused. Yet, the landscape is not unfamiliar.Humanity has been tossed about. Regardless of our medical and scientific experts attempts to control Nature’s emergent virus-child, the Novel Coronavirus, it has been an exhausting two-plus years for those of us who have survived. We mourn the losses of loved ones, of means of livelihood, neighbourhoods, sources of supplies and food, and importantly, patterns and rituals that we had always relied upon for comfort and support.

Our earliest traditions were arose from these reliable things of Nature: the sunrise, the sunset, the seasons. Weather patterns of the ancient lands where our beliefs and lore were birthed, are now, too, washed over with sand and debris. We dig to find and restore them. But they are weighted down, broken in places, and entangled with seaweed.

Our earliest traditions were arose from these reliable things of Nature: the sunrise, the sunset, the seasons. Weather patterns of the ancient lands where our beliefs and lore were birthed, are now, too, washed over with sand and debris. We dig to find and restore them. But they are weighted down, broken in places, and entangled with seaweed.

© Susan J Katz 2018 When I lived in the remote desert of the American southwest a few years ago, my family put up a stake of money for a lovely Oneg Shabbat dessert reception at the synagogue I attended, in honour of a significant birthday milestone. I was going to chant the haftarah, the weekly reading from the book of Judges, that I had chanted at my Bat Mitzvah so many decades before. On the day of the Oneg, I awoke at sunrise to get ready for the 1-1/2 hour drive into town to the synagogue. Looking out the window of my mobile home, I saw that a torrential downpour had come down overnight.

Knowing how fragile and exposed the desert roads were, I checked the news and internet for word about the possible closure of the one road we had that ran 25 miles before connecting to a highway and the rest of the world. There was nothing from the department of transportation or any other news, so I got dressed and drove.

After the first 10 miles I suspected the worst outcome to the road caused by the storm because so many trucks and cars were heading back into town. But, I kept on going: because I had to get there to chant the Haftarah and celebrate with my friends and indulge in all the goodies my family had arranged for me.

After all, I reasoned, I had my little truck, and experience driving in slush and snow and unmarked roads in Alaska and as a Forest Ranger – and there was no report of a road closure, no signs on the road to go back: Just those darned vehicles heading towards me and back into town. Of course, there it was: after driving 22 of the 25 miles towards the highway the road was completely gone.

The desert had completely swallowed up the road. Wet sand, Brittle Bush and Cacti sat quietly there in what once was our lifeline out to the world, as if they had been there all along. I saw two police cars, real tough Hummers, slipping sideways in the muck and finally giving up, almost like a pair of mud wrestlers trying to slog through to the finish. It made me feel a bit better, that I’d made it as far as they did in my little truck, but it was also clear that after driving 45 minutes already, then having to turn around and drive 45 minutes back, then risk another 2 hours over the mountainous back route, if it was even open, I was going to miss my lovely special Shabbat event.

The desert had completely swallowed up the road. Wet sand, Brittle Bush and Cacti sat quietly there in what once was our lifeline out to the world, as if they had been there all along. I saw two police cars, real tough Hummers, slipping sideways in the muck and finally giving up, almost like a pair of mud wrestlers trying to slog through to the finish. It made me feel a bit better, that I’d made it as far as they did in my little truck, but it was also clear that after driving 45 minutes already, then having to turn around and drive 45 minutes back, then risk another 2 hours over the mountainous back route, if it was even open, I was going to miss my lovely special Shabbat event.I drove back and passed our little desert airport, wistfully thinking about running into the little terminal shack and commandeering some pilot who might be sipping a quiet cup of morning coffee to fly me out to the synagogue, which shared a fence with a large airfield anyway. Energy pulsed through me to do that; but I knew the reality was that Nature had been busy overnight, and that although I would not be there, my friends would be enjoying the spread of delectable food and decorations on my behalf. Finally, the phones were working again, and I was able to get a call out to one of them and let him know about the road washout. As urbanites, it would be harder for them to visualize how it was even possible for a road to completely disappear, but when you live in the wilderness, deferring to Nature is the rule.

So, what is the subject of my post, ‘Work on What Has Been Spoiled’?

As we pick ourselves up from those pandemic years of being tossed about in waves of Coronavirus and slog up the beach, now castaways looking for something familiar, we are each likely carrying old expectations of what should be happening, or how things will look. But we all can see – they aren’t the same. We can try to force things to go as expected, as they had been before the flood, just as I had thought by running my little truck through the hopelessly washed away desert road to get to my duties at synagogue and my party. My idea of hijacking a pilot and flying into town would most likely have downgraded to me stealing an airplane and flying it, without any training in doing so.

As we pick ourselves up from those pandemic years of being tossed about in waves of Coronavirus and slog up the beach, now castaways looking for something familiar, we are each likely carrying old expectations of what should be happening, or how things will look. But we all can see – they aren’t the same. We can try to force things to go as expected, as they had been before the flood, just as I had thought by running my little truck through the hopelessly washed away desert road to get to my duties at synagogue and my party. My idea of hijacking a pilot and flying into town would most likely have downgraded to me stealing an airplane and flying it, without any training in doing so.The most likely outcome of such persistence in working things that have been spoiled, is to get stuck, get mad, and become very tired or fail. These days, people attempt to avoid this pain or failure with what is known as a ‘hack’. For example, taking a shortcut by making an illegal left turn onto a one-way street and then expecting everyone to get out of the way, and even blaming the law-abiding drivers of causing the resulting traffic jam.

As a friend put it, for the past many years we have been living in the, “I Got Away With It” culture.

If the ‘hack your way through and get away with it’ strategy is not appealing, I applaud you.

Our ancient wisdom texts have lovingly preserved stories for us to see and learn how to responsibly and morally respond to change. We can find a new way in our new world.

An ear worm, a loop of rhythmic words, has been circulating in my brain the past few weeks: it repeats, ‘Work on what has been spoiled’. In fact this is one name for Hexagram 18 of the I Ching, the ancient Chinese Book of Changes. ‘Decay’ or ‘A Can of Worms’ is another translation for this Hexagram’s name. The I Ching is a two thousand year old book of wisdom from East Asia, created to help us understand how to determine our actions in the midst of life’s constant and inevitable changes. From learning how to understand imagery and metaphor, rather than rely upon analytical thinking and problem solving, we can find out where we are in a situation, and thus make decisions on how to proceed.

An ear worm, a loop of rhythmic words, has been circulating in my brain the past few weeks: it repeats, ‘Work on what has been spoiled’. In fact this is one name for Hexagram 18 of the I Ching, the ancient Chinese Book of Changes. ‘Decay’ or ‘A Can of Worms’ is another translation for this Hexagram’s name. The I Ching is a two thousand year old book of wisdom from East Asia, created to help us understand how to determine our actions in the midst of life’s constant and inevitable changes. From learning how to understand imagery and metaphor, rather than rely upon analytical thinking and problem solving, we can find out where we are in a situation, and thus make decisions on how to proceed.I saw this cartoon and it caught my attention:

The figure of a sleepy man yawning on his way to work on the subway, suspended from the hanger still in his dress suit, is supposed to be funny. And, isn’t it so true? Boredom has set in where once competition and higher education had urged young minds to excel, to think outside the box and be curious and inventive and creative and courageous. Education meant to open our minds is now just an ornament to put on a job resumé to gain employment and go back to sleep.

The figure of a sleepy man yawning on his way to work on the subway, suspended from the hanger still in his dress suit, is supposed to be funny. And, isn’t it so true? Boredom has set in where once competition and higher education had urged young minds to excel, to think outside the box and be curious and inventive and creative and courageous. Education meant to open our minds is now just an ornament to put on a job resumé to gain employment and go back to sleep.Physical and mental challenges are an essential part of maturation and becoming responsible and ethical; and sadly, today, challenges are often met by getting by without them.

This is the underbelly of ‘Work on what has been spoiled’. Teaching your child how to do the hard work of their math homework rather than hacking a grade by doing it for them, is the way to nurture independence and engagement, rather than creating a bored working stiff, as in the cartoon above.

When we do these undisciplined, unsanctioned hacks, things decay, become decadent: instead of good food, the food cans now contain maggots.

I once met with a patient who had acquired a life threatening infectious disease. He was hospitalized, with no friends or family. He told me that he had been raised in one of the wealthiest families in the region, spent his time partying on the family’s yachts and skiing in the Alps and Aspen; all those things that were just the norm for him. They had servants and he never had any responsibilities. As a young man he decided to get a remote cabin in the mountains and live like the film character, Jeremiah Johnson, a backwoodsman, along with his girlfriend.

I once met with a patient who had acquired a life threatening infectious disease. He was hospitalized, with no friends or family. He told me that he had been raised in one of the wealthiest families in the region, spent his time partying on the family’s yachts and skiing in the Alps and Aspen; all those things that were just the norm for him. They had servants and he never had any responsibilities. As a young man he decided to get a remote cabin in the mountains and live like the film character, Jeremiah Johnson, a backwoodsman, along with his girlfriend.Although still young, his health began to fail: his earlier, carefree partying days of sharing drug needles and bodily fluids with others had given him some diseases that weakened him so much that his leg broke while out hiking. His dog helped him get back to the cabin, but his girlfriend abandoned them. So, there he was, alone and very sick. Eventually some neighbours brought him into town and he made it to the infectious disease ward for treatment.

He said he had no skills for living: everything had been given to him with no challenges his whole life. He saw the folly of shirking any education in even the basic skills for taking care of oneself all too clearly.

Recognizing where one is at is the first step toward finding your way forward. This patient was ready and eager to begin work on what had been spoiled.

This topic is relevant to the New Year of Autumn. We get a chance, before or even after, finding ourselves lost and injured in a snow bank, to reflect on what we have learned this past year, and how we can move forward better in the new one. That patient had been raised to shirk responsibilities and assign blame to others for any problems or shortfalls. Now, in his solitude, he could see that he alone was in charge of his decisions after all, not others. Saying “I can do better and want to be responsible” was the most powerful thing he could do for himself.

The Hexagram, ‘Work on What Has Been Spoiled’ is not about what has been Spoiled: it is about Work. Just as moving forward into the world after the pandemic is not about what the Coronavirus did to us; it is about the honest work, without blame of oneself or others, and of adapting to a changed world.

Work is hard! with guidance from our ancestors and choosing to engage with the lessons in their books of wisdom, we, too, can see how to move forward, with awe and wonder and pride, and with reflection.

May your New Year be filled with growth, with wisdom from our elders, and a promise for the future.

Shana Tova…Susan J Katz

-

A Reed for the New Year

The Jewish New Year holiday of Rosh HaShana begins this evening at sunset. It is an auspicious time of reflection on the past year and what went well, and even more importantly, what did not. We are encouraged, through our traditions and liturgies, to go even further; and examine the things we ourselves did that perhaps made things not go well for not only for ourselves, but for others.

As time moves on, so do traditions. Communal prayer, which replaced the animal sacrifices of Judaic Temple times, was considered a time to be with others to pray and reflect on our relationships with God, with self, and with others. Full prostration by not only the prayer leaders, but congregants as well year ’round, was not uncommon, such as during the Aleinu prayer. Tears and beating one’s chest over the heart, and other gestures, covering the head in a prayer shawl or scarf, provided solitude, as well.

Things have changed, though. Prayer spaces are crowded during holidays, and priorities as to what we show to others have shifted. Long services often become a time for restless shuffling of nearby congregants, scrolling on mobile phones, thoughts of luncheon meals and guests, as well as tempting redirection away from deeper or painful thoughts towards uplifting songs and instrumental music from the prayer leaders.

Let’s face it: it’s hard to do ‘deep reflection’! A relative used to glibly say, wineglass swaying in her hand, “Why would anyone want to do something hard if they don’t have to?”

Yes, why would they?

I’ve opened this post with the usual, annual, Jewish invitation to ‘reflect deeply’. It’s hard, and where are the instructions! I agree. So here is one way to think about it….

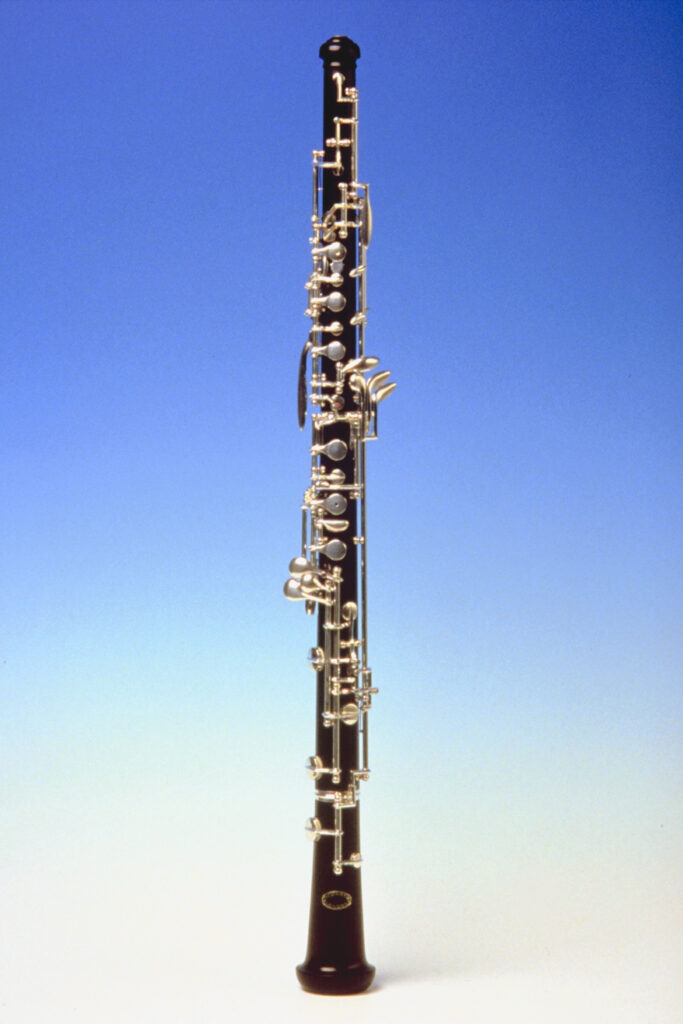

The one thing that defines the personality and angst of being an oboist, far above anything we do or create, is our Oboe Reeds. Finding or making or being gifted the Perfect Oboe Reed is the ultimate quest for an oboist. Why is that?

An oboe, the long wooden conical bore with keys on it, a bell at one end and an opening to blow through at the other, is not the part that makes the gorgeous, plaintive, oboe sound. It is the reed that allows the correct and perfect sound to move through the bore with the correct selection of keys for each note, become amplified into warm, dark, sumptuous sound waves, and gracefully round itself as it resonates through the bell. With an unresponsive reed, one that is too hard to vibrate naturally or too soft to hold its shape under embouchure pressure, the sound is, well, lousy. Quacky, like a duck, which is what beginner oboists are often accused of sounding like.

So, there are a few things going on that an oboist has to control: the quality of the instrument; good habits with regard to embouchure, breath control, and fingering of keys; and using an excellent reed.

It’s not too hard to acquire a good instrument, although they are expensive! I happen to own a wonderful Violetwood oboe that plays like a dream. However: Embouchure, breath, and fingering control are built and maintained by quality instruction in technique, and you guessed it: tons of practising those techniques!

That leaves the bane of all oboists: the reed. It’s really hard to make or buy a perfect oboe reed. Making them requires good tubes of cane, and then gouging them to the right thinness, and then assembling and scraping the blades down, but not too much….You can buy a really good one, but it will still need your expertise to perfect it. The oboist will still need to have a good well-sharpened reed knife to whittle away on it, correctly, testing it at each slight scraping away of the cane until it feels and sounds perfect.

My teachers always emphasized the primary directive of adjusting the reed to the player, and not vice versa. Settling for a bad reed, one that is not responsive, or plays too flat or too sharp, means monkeying around with your breathing, posture, embouchure, fingering, in order to get a decent sound out of it. In other words: the reed is controlling you.

In the process of doing all these contortions, to the point of losing all your hard-earned good technique, you are no longer making your music. You are relinquishing your unique identity and timbre of sound, your signature as a musician, in order to produce instead an adequate sound, from a poorly crafted piece of cane. Your ability to play as a unique and expressive musician and muse of the instrument are the cost of this battle for control of the instrument. Convenience has won out.

Again, back to my wineglass-waving relative. “Why would anyone want to do something hard if they don’t have to?”

Making reeds is hard! Making excellent reeds is even harder! But, as musicians, driving to capture the correct sound for who we each are, it is imperative to strive to make them. Or else, we are lost to a poorer quality sound of convenience.

Just like the oboist, we must patiently and attentively whittle at those rough places. The easier ways out – of letting the reed, or the situation, or that other person, control you – will cost you your self-hood.

I recently received an email advertising a master class in learning how to adapt to and play with low quality reeds. Imagine! The premise is: that bad reeds abound. They come from making them without enough expertise or good materials; or else we buy them, and are unable to finish them well. Either way, this reed hack master class will teach you how to distort and bend your good habits and technique in order to play low quality reeds.

I immediately thought of my teachers, often correcting me for doing just that: trying to get a good sound out of a bad reed, thus sacrificing the hours and hours of hard work I’d done to develop good technique in the process. Those reeds, they said, needed to be either adjusted or replaced.

Looking at this past year now, and the unknowable that will unfold ahead, how will you adjust your reeds? will you adjust yourself further and further to meet the needs of reeds or situations that are unsuitable? or take the opportunity this time of year sets aside and do the satisfying work of refining these situations and yourself, forming lovely reeds for playing your song?

I wish you all a year of good music, for yourself and with others, and all the joy and connections that music brings your way.