-

Bikur Holim: Tips for Patients and Their Helpers

Have you ever been ill and found your friends and family lacking in skills to help you? or, as a helper to someone who is ill, been frustrated and wished you had more knowledge about how to be helpful? This is the case for most of us, if it strikes a chord with you, too, read on….

In 2013 I published a post about this topic, Bikur Holim. It is time for a refresher, with more thoughts and tips to help you establish who you are, what your needs are, and how to communicate them best.

It might surprise you to know that there are guidelines available for being a patient or caregiver. Yes, that’s right, you don’t have struggle with asking for what you need as a patient, or guess or worry about what to do or of making a mistake because you are winging it. I’m going to write mainly about Jewish practices for visiting the sick, Bikur Holim, but you don’t have to be Jewish to use them.

I actually feel it is my duty, with all my professional knowledge and experience, to share what I know on this most important topic. My professional specialty is to be present for people who are ill and their supporters, whether in hospital, or in my office where we can meet for spiritual care and counselling. This is a ministry that I have many years of accredited study in, as well as work experience. I have also spent a few years on the care receiving side, as a dis-abled person. I know the territory well from all angles.

So, let’s start with those of you who are well persons, who have never been ill or dis-abled enough to need help from others. And, by ‘others’, I am not referring not only to healthcare professionals, but non-professionals, such as family, friends, faith community, neighbours.

Here’s an example: You know someone who is not well and you want to help them. You know you can do this, too, because you are a good person. You have your religious faith and morals and ethics, and you are a compassionate person, thinking of others and making the world a better place.

Is being a good person with good intentions enough, though?

It may surprise you to learn that this in itself is not enough! Being a good person who wants to help is the first step, an essential foundation, but actual skills are needed. There are dynamics involved between you and the ill person that must be understood and accepted, and enacted.

In fact, if your only impetus for providing care is that you believe yourself to be a good person or been told you are a good person, you may also believe that what you are doing must also be good. You may have been told that helping others is a good deed and that doing this good deed will put you in good stead with your faith, or with God. The truth is, though, that you may do more harm than good, and you may be drawn to this post because you have already found that out and want to do better and have some skills.

It is important first of all, to sort out in your mind whose needs you are serving: yours or the ill person’s. This may sound astonishing at first, but if you take a moment to look within, you can find the answer.

I suggest this because helping others well can only be accomplished by listening to what they tell you they need, and not vice versa. An example would be offering a patient a ride home from the hospital, but then burdening the sick person with restricting the ride to when and how it is convenient for you, e.g. making them walk on their own to the entrance to meet you at the curb on your way to errands, and then dropping them off at their door withut escorting them inside if they are having trouble ambulating. Or offloading your offer onto a stranger who may or may not show up, because you are too busy. Imagine, well person, that you have just had surgery and are weak and in pain, and have to get yourself to the hospital lobby and wait until your ride home arrives, ambulate to their idling car at the curb, make your way into your home after being dropped off, put yourself in bed wishing you had the energy to make a cup of tea or a bite to eat. Imagine that. Putting yourself in the patient’s shoes as you offer help can be a good idea.

Once you have taken this step, you are released to turn your intentions towards attending to the ill person.

A corollary to making poor arrangement is ‘Don’t offer help unless you are willing to listen to the needs of the patient and follow them’. If you cannot, let the patient find someone who can. Sometimes, when ill, it is hard to ask for help, and it is easy to feel shame for turning down help that is offered but inappropriate: when ill, we are vulnerable, already in pain and suffering. Torah tells us in Leviticus 19:14 not to place barriers before someone who is dis-abled.

I just provided some basic general rules. There are more specific ones as well, here is a source of study for Jewish traditions in Bikur Holim

People are all different, so you may not know that offering to pray for healing is less important than doing their dishes and laundry. Patients can and often do, pray on their own. Ask what needs to be done rather than making assumptions, unless the person is unable to speak. Another example would be dropping off a packaged kosher meal for Shabbat for the patient to eat alone. Was this food really needed? Will leaving this this packaged food to be eaten alone on Shabbat count as a good deed? Alternatively, ask, “do you need food for Shabbat” or better, “do you want company for Shabbat?”

In every case, the common thread is: ask. If the sick person declines your offer to bring food they don’t need, or a ride that will not fit with discharge planning, gracefully accept their honesty wth you. When ill, energy is being expended on healing, leaving little for resisting pressure to make agreements that aren’t appropriate or are creating guilt for not helping the helper feel good. We have all heard the saying, “The road to Hell is paved with good intentions”! Good intentions require good skills to create good outcomes.

Patients, you can help yourselves by doing a few things as well, too.

Create lists of specific things you want and share them. This way, you will reduce the guesswork or uninvited offers aimed your way, and you have more control over your care.

Set boundaries, for example: tell visitors not to sit on your bed, list what you can and cannot eat, list dates and times that you need transportation, and be assertive and stand firm when someone wants to put their needs over yours.

We think of elders and dis-abled people as being weak or timid. Not true! Bette Davis is known to have said, “Getting old ain’t for sissies”. The same can be said about being ill. As Paul Caune says is his film, ‘Hope is Not a Plan‘, “When you have a disability, you have to be tough to survive.”

One of my favourite films depicting the plight of a hapless patient in the hospital being visited by a well-meaning, self-fulfilling friend, is this 1932 Laurel and Hardy classic film, “County Hospital“. Study this film and drink in all the ways that this visit goes wrong!

In Judaism, we have full texts on Bikur Holim, or Visiting the Sick. If you want to learn more about this important duty, let me know. It will be my pleasure to study this topic with you, or a group of others who are interested.

Thank you for reading, and may you bless and be blessed by those who are in need.

-

Scheherazade

I was speaking with someone recently who had a challenging exam coming up and did not feel ready. The teacher insisted she be there and take the exam. Despite all the reasons she could summon to postpone, he compelled her to be there. She passed with flying colours. How? she thought about someone important to her that had recently passed away, and decided to dedicate her endeavour to the memory of that person.

This reminded me of a similar experience I’d had many years ago. My Tai Chi Chu’an instructor had been called and told by his teacher, the venerable Grand Master who’d brought traditional martial arts of the 1930’s China to North America, that he was to bring his students to a banquet in his honour, and demonstrate what he’d been teaching us. It was a daunting proposition; we three senior students rehearsed the 108 steps, a Wu-Yang combined form, for weeks. We got our outfits organized, and hoped for the best.

The banquet was in an enormous Chinese restaurant in Vancouver, with over 400 guests. The demonstrations were to be held on a small dance floor, a tiny lit up showplace for for all the guests to revel in and be dazzled by the proficiency and nerve of the students and teachers that the Grand Master had produced in his 20 years in Vancouver.

By the time I arrived at the restaurant, with my special jacket slung over my arm, my teacher was already there. I was ushered over to his table. The ‘Three Musketeers’ as the three of us had started to call ourselves, were not unaware of the spectacle we were about to become part of. One was just plain talking nonsense to ease his nerves, and the other was resigned to ‘it is what it is’. I had rehearsed the form so many times that my brain couldn’t hold any more pictures of how to do it. We put on our jackets behind a screen and waited for our turn, at our seats.

Suddenly, we were signalled to go to the spotlighted floor. We stood on the precipice between the carpet and parquet, then for a moment looked at each other more like the Three Stooges. I didn’t want to us to be stooges, though. Our teachers had honoured us with imparting their wisdom, truth, and patience, and I wanted to honour them by showing this austere martial arts community that we were fully trained and awake. We stood in our places, and took a breath together and then began. ‘Raise hands…’

I felt the fluid rise, fall, carry, circle, beauty, grace, touch, light, heavy, breath in and out with each step for 108 movements. Time and place slipped away until I came to a close just where I began, and bowed, hands held towards the Grand Master, our Teacher, and the audience, in proper kungfu gesture of respect. My comrades were looking sheepish as we walked back to our table. Something unexpected then unfolded,

Along the way back, people smiled and reached towards me. When we sat, my teacher had me sit next to him. Beneath his thick moustache, his mouth grinned, dimples deep in his cheeks and face blushing. He tapped my hand, then closed and opened his eyes with a nod of silent praise. We were almost the last on the floor demonstrations, and straight away, the Grand Master began circulating to the tables to have photos with his guests. He first came to our table. I assumed it was to honour my teacher for bringing his industrious, intrepid students. Which was true: but instead of standing next to my teacher for the photos, he stood behind me for all of them! My teacher beamed with pride, to have succeeded so well with his students that his own teacher honoured one so.

I forgot about this for almost ten years, and went my own path; my teacher got me a job and told me my students would now be my teachers. I decided after so many years to have lessons with the Grand Master. I entered his little ground floor studio. There were students practicing tui shou push hands and other exercises, and the Grand Master was at the back giving a lesson to someone, with push hands. He looked sideways to glance at whoever had just come into the studio door, and abruptly dropped the hands of the student he was teaching and walked over to me. He gently took my hand and asked, “What your name?” I told him “Susan”. “Ah, Soo-san, Soo-san”. Smiling he took me over to the wall, which had photos plastered over it. In one section, he had photos of that banquet from 10 years ago, and there I was, in several of them! He pointed, “Soo-san” and smiled. He remembered.

He started me at what they called the ‘Dragon’ level. He did not have me learn his form from the beginning. I was told the no one, in the decades since he had been there, had ever been allowed to skip learning his form. I tried to be like everyone else and make small talk with him, about which restaurants had the freshest fish or where to buy the best sword. If I tried to speak to him in my lessons, he would take my hand abruptly and sit me down on a bench and say, “Sit, drink tea”. Oops. He taught me in silence, and I listened as he guided, prompted, pushed, pulled and showed me how to master movement and energy.

Today, I played my favourite oboe exerpts from Rimsky-Korsakov’s ‘Scheherazade’. It is the first time I have done so since sustaining injuries many months ago. It was scary; my attempts to play music thus far had been choppy and jumbled as my brain and body endeavoured to reassemble in harmony. Going back recently to Tai Chi, as a student at a new dojo with a new teacher, has been a boon. But, today was about the oboe and about music. I thought of my beloved oboe teachers and their important words, to play everything, including technical exercises, with expression; that is how music is played, otherwise, it is merely notes.

I played Scheherazade companioned by their lessons and words, coyly coaxing out lyrical music, a ballet ship afloat over crestfalls and sea.

-

Learn to Ride, Learn to Change

Yesterday I had the pleasure of watching a father teach his daughter how to ride a bicycle. How special to witness this big event!

At first, their endeavours didn’t look too promising. They were on the field track with several signs posted: ‘No bicycles allowed’ and ‘No cycling allowed’. There are good reasons for this ban on bicycles, including protecting folks like myself, who choose to walk on a track rather than the nearby trail in order to avoid hazardous, avid, or undisciplined cyclists. But in this case, Dad was calm and easygoing and responsibly aware of those around him and his cycling daughter.

After walking several laps, things looked as if they were going along pretty well with the bike lesson. Nonetheless, my mind beamed coaching tips towards the Dad, “Run faster as you push the bike along” and towards the daughter, “Keep pedaling, don’t stop pedaling!”

At my penultimate lap, there they were: Daughter launched with one last push from Dad, and suddenly pedaling like a pro! What a thrill! Dad praised her over and over with ‘Way to Go!’ ‘Great job!’ I echoed his words to both of them and he proudly told me it was her first time riding solo. As the witness to the joyful event, I gave them two thumbs up. Way to go Daughter, and Dad.

Sometimes, it is not a parent or other who who fosters our success. A friend once told me the story of how she taught herself to ride a bike at age 8. Her father had tried to teach her years earlier, and having failed, said to her, “You’ll never ride a bike, I give up”. By the time she was 8, it became imperative for her to learn, if not to keep up with her outdoorsy friends, then for self-esteem. She taught herself by repeatedly scooting the bike, a present from her 5th birthday, down the driveway and then pedaling hard down the ramp and into the street, until she was suddenly cycling on her own. The secret, she learned, was not to focus on the past failure: but to just keep pedaling.

This is the model for how we bring change into our lives, by continuing to pedal, regardless of whether Dad is pushing you along, or you discover your ability on your own. As with the little girl, Dad was important for a while, but had to let go of the bike for her to discover her ability to ride on her own. But the fond memory of her patient, easygoing Dad helping her undoubtedly will remain and guide her in so many new endeavours and undertakings in her life. Others, such as my friend, will recall what inner guidance system brought success as they navigate new challenges.

Even in turbulent times, it is essential to remember: the only thing that is constant is change. We count on so many things to be sources of stability, and can become distressed without a familiar pattern or routine. Someone jokingly once told me that the only ones who like to be changed are babies!

But the truth is, that ultimately, to thrive, we must pedal forward with tenacity, courage, and joy into the unknowable future.

Think of all the places you can go when you learn to navigate and accept change!

-

Fear, Danger, Winter, Light

I was recently reading Sarah Polley’s book, Run Towards the Danger. It was the title that grabbed me as I browsed along the shelves of our librarians’ weekly picks. Run towards the danger I thought to myself. The title came from advice given to her by the physician who was treating her for concussion.

The tendency to avoid unseemly noise and bothersome lights is exaggerated when one’s nervous system is disrupted by a concussion. Even small sounds, if at the wrong frequency, can be devasting. I know this from my own experience, and the last thing I would have guessed to do would be to run towards such dangerous sensory triggers, rather than avoid them and allow a gradual desentitization to occur.

I liked this theme, this new approach to rise and challenge that which is making life constricted and small. When senses are over reacting and indicating to the mind that something benign is unsafe, life becomes very contained, and the more you obey these danger signals, the smaller your living room becomes. I liked her doctor’s approach. It felt liberating and empowering, and, as Polley writes, it is not just applicable to concussion treatment.

This time of year, media representations of who we are supposed to be, how to socialize, what we will experience, eat, and even what we are to believe. Our sensory lives are taken up with subtle and overt messages that may or may not, miss the mark of our real life experience. How do we navigate what may feel like too many messages, noise, or information?

It would be cliché to say that this can be a difficult, as well as fulfilling, time of year. The traditions of many people come at this time in the northern hemisphere of shortest days and longest nights. We gather to light candles that increase in numbers as the days grow longer; we celebrate the soltice as it turns from the longest night into lighter, longer days; we celebrate messages of birth and hope of a better future. Gathering to feast is a most human way of communally acknowledging these natural wonders and changes.

Some of us plan all year for this season, finding bliss and fulfillment when it arrives and along the journey there. Others find it difficult, or avoid it altogether.

As a hospital Chaplain, I liked to spend Christmas Day filling in for my Christian colleagues so they could spend the time with their families. I would be called from one site to another in the hospital’s system, from the ER to the long term care home. There would be a son who faked a car accident so that his father wouldn’t know he’d actually stolen the family’s TV, or a Vietnamese priest who was all alone with no visitors in the care home on Christmas, or a child whose parents were in the midst of a nasty child custody dispute and aggravating his illness. I would step into these spaces with all of my hours of training and supervision and clinical experience, and mostly with deep reverance, and create a safe, sacred, space; for the danger to arise.

And, yes, it would arise. And, yes, the participants all ran towards the dangers they presented with, because they wanted relief from the fears that held them hostage within themselves and to each other. The wayward son confessed, and his father could chastise and then make up with him; the priest welcomed my company and became comforted and less isolated; and the child’s parents admitted their marital frustrations and stopped bickering at their ill son’s bedside.

Some danger is good to run towards. Having a guiding presence, such as Polley had with her physician, or a professional Chaplain or Spiritual Director or other clinician, can help make it possible to shine light on what seems dangerous, to help turn the darkness and danger into a passage of discovery and healing.

-

Maintaining Your Light

For many places around the globe, last week began the switch from Daylight Saving Time to Standard Time. While we still have approximately 24 hours per day either way, I did hear a TV weatherperson say that the days will now be shorter. Likely, she meant that sunset will be an hour earlier on our clocks, foregoing the news that the sunrise will also be an hour earlier.

Why am I writing about personal light today? I have been in a muddle lately. I even understand much of the reason for this: my life being stalled by those who thrive on blocking out or stealing other peoples’ light. Because of the sheer volume of such interfering that has come at me in a short amount of time, I have begun succumbing and dipping low, no longer able to notice the pulling and continue on my way forward.

A look at ancient texts for insight and solutions is in order!

Last week’s Torah portion was Lech L’cha, which can be translated as, ‘Go Forward’ or ‘Go, Get Yourself Moving’. It follows the Torah portion of the previous week, “Noach” where we met Abram, who had settled with his family in Charan. Abram listens to God, and then at age 75, Abram Goes Forth. Being impulsive is rarely a good thing when making major changes, especially for the elderly! We may not know what lies ahead, but knowing that where you are or have been is no longer serving you well, this is the important first step. Abram followed the instructions of a formless Voice, he had context and a mission, and did not move on a whim or a guess.

It can be hard to move out of a place that you’ve always known, even if you’ve outgrown it, or just never felt right in. Becoming stuck or immobilized could be due to being bogged down or sapped of your energy by others: this is not an uncommon problem. In fact, there are many books available about this, about ‘energy vampires’ and light robbers. It is prudent to learn how to identify these people in order to mitigate their dampening and draining effects on you that can impair you from moving forward in your life and purpose. This is how I was feeling.

It’s not that easy sometimes to identify who is creating a drain or what barriers you are tolerating as you fail to stay on track with your goals and purpose. Lucky for us that our ancestors left us their tools!

We talked about the Torah portions of the last two weeks and I urge you to look at those for insight.

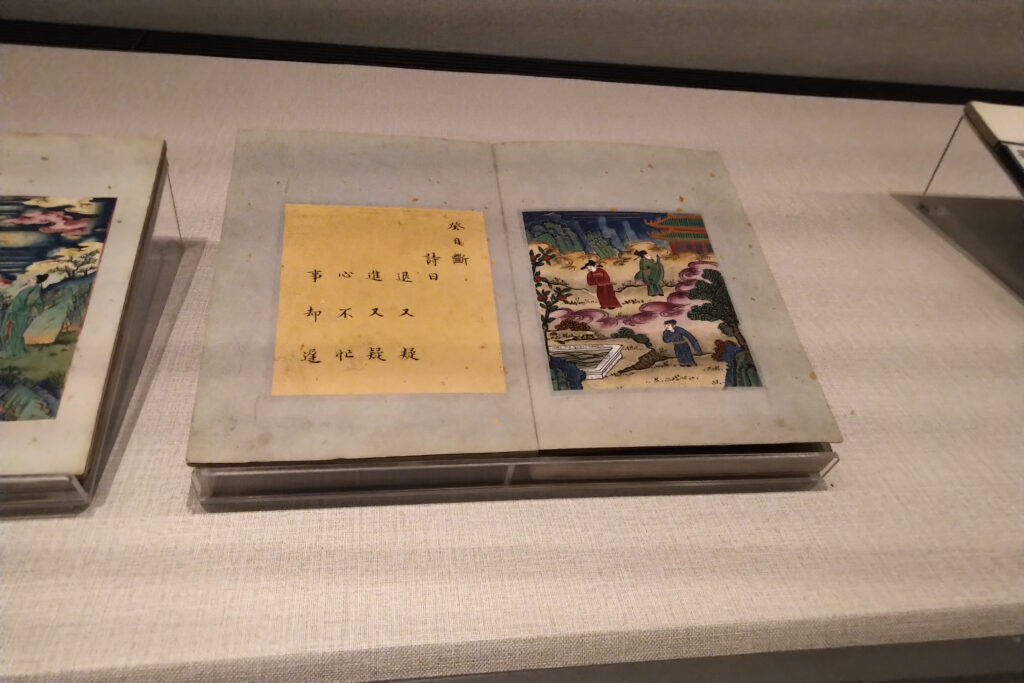

Yi Jing page, Taiwan National Museum ©susan j katz Another book that can be very helpful with understanding where you are at in a process is the Yi Jing or I Ching, which can be translated as the Book of Changes. This book contains 64 collections of lines called ‘Hexagrams’, each of which details six steps toward resolution of recognizable situations, such as Decay or Difficulty in the Beginning or Coming to Meet. It is a complex book that requires studying with an expert, and I had the privilege of studying at both the undergraduate and graduate academic levels with Dr. Titus Yu when he served on the faculty of a Canadian university.

Today, with having lost track of how problems were arising or where they were taking me, I turned to the I Ching. Sometimes, by knowing what the the problem is, it is possible to know which Hexagram to read. But, being blind to any insight, I proceeded with the traditional yarrow stick counting procedure that would produce a Hexagram for me.

The I Ching does not tell fortunes Now, there is some false belief that the I Ching is a book of fortune-telling and divination. It is not, and certainly not any more than the Torah or Bible are. This misrepresentation came about when the Book was introduced to North Americans during the glorious hippie days of the ’60’s and ’70’s, when everyone ‘did tai chi’ and ‘tossed coins’ to get their fortune told via this inscrutable and mysterious Chinese book of fortunes. The divination misconception persists in North America. In fact, I was recently at a Jewish farm centre that had an abundance of yarrow growing wild on its acreage, and I suggested that the farm harvest and dry the yarrow stalks to sell for those who use the I Ching as some much needed farm income. They declined, saying that the I Ching was a religious book of divination, forbidden in Torah, and could not be promoted by them. It is a shame that this great book of wisdom has been cast as a cookbook for fortune telling.

© susan j katz 2024 Sorting yarrow stalks to determine a Hexagram is quite involved and tedious, and it is meant to be that way. Briefly, fifty yarrow stalks are gathered and divided and counted in a precise system that uses both the right and left hands and fingers of both hands. In psychological parlance, both sides of the brain are being engaged. The lengthy time for the formulaic repetition and manipulation of the stalks allows the brain to move to into subconscious realms. You always start with a question, a very precise question, and keep it in mind as you process the stalks. This allows the brain’s linear and non-linear processes to integrate, and the inner answers that once were obscure, can now be understood. We indeed, have the answers within us. The I Ching helps us to access them. No intermediary person is needed.

The first Hexagram I obtained was ‘Conflict’. Rats! I thought, my problem has nothing to do with conflict! But, with faith that that there was something there for me, having made those piles of stalks over and over again, I read on. Only the two moving of the lines in this Hexagram had to be read. The text at the second step reads that it is important to step back when it is clear that a conflict can not be won, and that this retreat brings no shame, and could save one’s village from damage as well. The other line text says that the correct action at a stalemate is to go to an impartial authority or judge to resolve a conflict and to not pursue it further.

These two moving lines must then be transformed to form a new Hexagram. This one is called, ‘Progress’. The image of Progress is:

The sun rises over the earth

The image of Progress

Thus the superior man himself

Brightens his bright virtueAccording the the I Ching, we are all born with tremendous good light and purpose. As time goes on, we lose much of this, often due to the acts of others. The superior person learns how to move forward without losing their light to others. One way is to use one’s brightness to become a leader who gathers others together to honour a higher sovereign, bringing unity and reward to all. The alternative, of shining your light merely to be seen or for reward and praise, creates acrimony, rejection from those in charge, and loss of brightness.

As you see, in the I Ching, there are no specific answers or instructions given for your situation, such as stock tips or messages from deceased relatives. Instead, there is universal imagery for you to discern and find clarity to your answers, that already lie within yourself.

A third way we can lose our energy and potential through others is told in the indigenous allegory of the stick/mud/corn people. The corn people want to climb high in the sky, and the stalk people are the helpers that allow them to climb higher than they could on their own. Thus supported on a stake, the corn thrives. But, then there are others below who are jealous and see the weakness in this system. They do not see that being a mud person is also a good and natural path, just as a being a corn or stalk person is a natural path. The mud folk make the over extended stalk people fall over, and if not strong on their own, the corn people also fall down to the mud level. To remain aloft, one must have strength and clarity.

If you find you have lost your energy or focus or motivation, consider these stories. Who are you? What is clear for you and what is not? when did things slow down or stop? was anyone else involved? You can learn a great deal about how to proceed, reclaim lost focus, and bypass interrupters to continue to shine your light.

By the way, you wish to learn more about the I Ching, please don’t hesitate to reach me through my contact form, or send me an email request: susan at susanjkatz dot com.

We are born full of brightness and light. These books of our ancestors help us know how to preserve clarity and share our wonderful gifts, and avoid the dampening forces of others.

Lech L’cha, Go Forth and Shine Your Light!