-

Scheherazade

I was speaking with someone recently who had a challenging exam coming up and did not feel ready. The teacher insisted she be there and take the exam. Despite all the reasons she could summon to postpone, he compelled her to be there. She passed with flying colours. How? she thought about someone important to her that had recently passed away, and decided to dedicate her endeavour to the memory of that person.

This reminded me of a similar experience I’d had many years ago. My Tai Chi Chu’an instructor had been called and told by his teacher, the venerable Grand Master who’d brought traditional martial arts of the 1930’s China to North America, that he was to bring his students to a banquet in his honour, and demonstrate what he’d been teaching us. It was a daunting proposition; we three senior students rehearsed the 108 steps, a Wu-Yang combined form, for weeks. We got our outfits organized, and hoped for the best.

The banquet was in an enormous Chinese restaurant in Vancouver, with over 400 guests. The demonstrations were to be held on a small dance floor, a tiny lit up showplace for for all the guests to revel in and be dazzled by the proficiency and nerve of the students and teachers that the Grand Master had produced in his 20 years in Vancouver.

By the time I arrived at the restaurant, with my special jacket slung over my arm, my teacher was already there. I was ushered over to his table. The ‘Three Musketeers’ as the three of us had started to call ourselves, were not unaware of the spectacle we were about to become part of. One was just plain talking nonsense to ease his nerves, and the other was resigned to ‘it is what it is’. I had rehearsed the form so many times that my brain couldn’t hold any more pictures of how to do it. We put on our jackets behind a screen and waited for our turn, at our seats.

Suddenly, we were signalled to go to the spotlighted floor. We stood on the precipice between the carpet and parquet, then for a moment looked at each other more like the Three Stooges. I didn’t want to us to be stooges, though. Our teachers had honoured us with imparting their wisdom, truth, and patience, and I wanted to honour them by showing this austere martial arts community that we were fully trained and awake. We stood in our places, and took a breath together and then began. ‘Raise hands…’

I felt the fluid rise, fall, carry, circle, beauty, grace, touch, light, heavy, breath in and out with each step for 108 movements. Time and place slipped away until I came to a close just where I began, and bowed, hands held towards the Grand Master, our Teacher, and the audience, in proper kungfu gesture of respect. My comrades were looking sheepish as we walked back to our table. Something unexpected then unfolded,

Along the way back, people smiled and reached towards me. When we sat, my teacher had me sit next to him. Beneath his thick moustache, his mouth grinned, dimples deep in his cheeks and face blushing. He tapped my hand, then closed and opened his eyes with a nod of silent praise. We were almost the last on the floor demonstrations, and straight away, the Grand Master began circulating to the tables to have photos with his guests. He first came to our table. I assumed it was to honour my teacher for bringing his industrious, intrepid students. Which was true: but instead of standing next to my teacher for the photos, he stood behind me for all of them! My teacher beamed with pride, to have succeeded so well with his students that his own teacher honoured one so.

I forgot about this for almost ten years, and went my own path; my teacher got me a job and told me my students would now be my teachers. I decided after so many years to have lessons with the Grand Master. I entered his little ground floor studio. There were students practicing tui shou push hands and other exercises, and the Grand Master was at the back giving a lesson to someone, with push hands. He looked sideways to glance at whoever had just come into the studio door, and abruptly dropped the hands of the student he was teaching and walked over to me. He gently took my hand and asked, “What your name?” I told him “Susan”. “Ah, Soo-san, Soo-san”. Smiling he took me over to the wall, which had photos plastered over it. In one section, he had photos of that banquet from 10 years ago, and there I was, in several of them! He pointed, “Soo-san” and smiled. He remembered.

He started me at what they called the ‘Dragon’ level. He did not have me learn his form from the beginning. I was told the no one, in the decades since he had been there, had ever been allowed to skip learning his form. I tried to be like everyone else and make small talk with him, about which restaurants had the freshest fish or where to buy the best sword. If I tried to speak to him in my lessons, he would take my hand abruptly and sit me down on a bench and say, “Sit, drink tea”. Oops. He taught me in silence, and I listened as he guided, prompted, pushed, pulled and showed me how to master movement and energy.

Today, I played my favourite oboe exerpts from Rimsky-Korsakov’s ‘Scheherazade’. It is the first time I have done so since sustaining injuries many months ago. It was scary; my attempts to play music thus far had been choppy and jumbled as my brain and body endeavoured to reassemble in harmony. Going back recently to Tai Chi, as a student at a new dojo with a new teacher, has been a boon. But, today was about the oboe and about music. I thought of my beloved oboe teachers and their important words, to play everything, including technical exercises, with expression; that is how music is played, otherwise, it is merely notes.

I played Scheherazade companioned by their lessons and words, coyly coaxing out lyrical music, a ballet ship afloat over crestfalls and sea.

-

A Reed for the New Year

The Jewish New Year holiday of Rosh HaShana begins this evening at sunset. It is an auspicious time of reflection on the past year and what went well, and even more importantly, what did not. We are encouraged, through our traditions and liturgies, to go even further; and examine the things we ourselves did that perhaps made things not go well for not only for ourselves, but for others.

As time moves on, so do traditions. Communal prayer, which replaced the animal sacrifices of Judaic Temple times, was considered a time to be with others to pray and reflect on our relationships with God, with self, and with others. Full prostration by not only the prayer leaders, but congregants as well year ’round, was not uncommon, such as during the Aleinu prayer. Tears and beating one’s chest over the heart, and other gestures, covering the head in a prayer shawl or scarf, provided solitude, as well.

Things have changed, though. Prayer spaces are crowded during holidays, and priorities as to what we show to others have shifted. Long services often become a time for restless shuffling of nearby congregants, scrolling on mobile phones, thoughts of luncheon meals and guests, as well as tempting redirection away from deeper or painful thoughts towards uplifting songs and instrumental music from the prayer leaders.

Let’s face it: it’s hard to do ‘deep reflection’! A relative used to glibly say, wineglass swaying in her hand, “Why would anyone want to do something hard if they don’t have to?”

Yes, why would they?

I’ve opened this post with the usual, annual, Jewish invitation to ‘reflect deeply’. It’s hard, and where are the instructions! I agree. So here is one way to think about it….

The one thing that defines the personality and angst of being an oboist, far above anything we do or create, is our Oboe Reeds. Finding or making or being gifted the Perfect Oboe Reed is the ultimate quest for an oboist. Why is that?

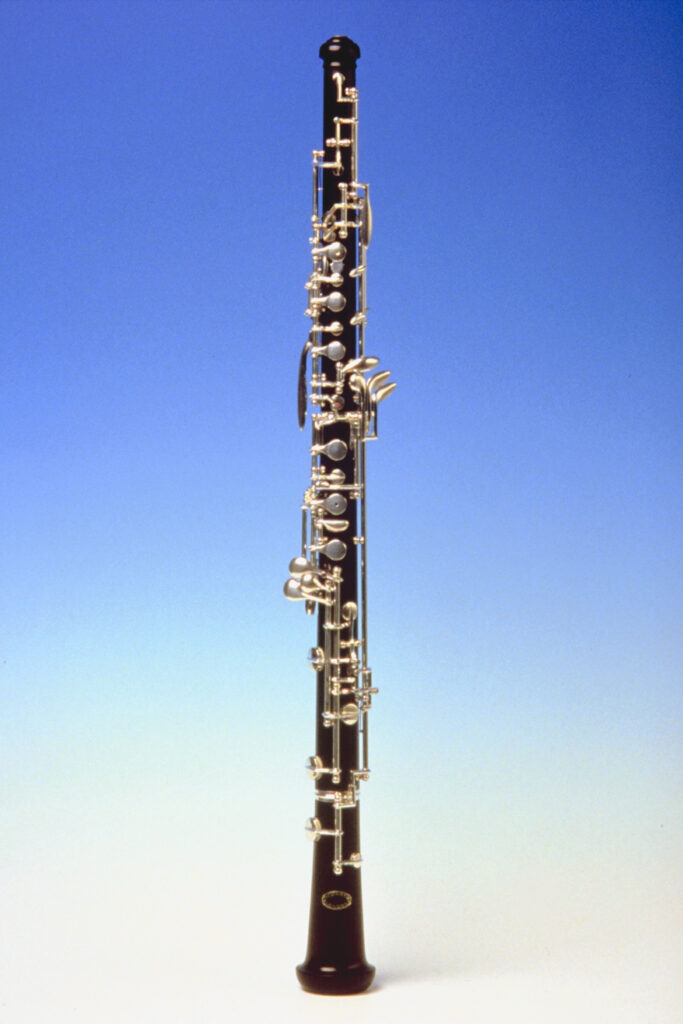

An oboe, the long wooden conical bore with keys on it, a bell at one end and an opening to blow through at the other, is not the part that makes the gorgeous, plaintive, oboe sound. It is the reed that allows the correct and perfect sound to move through the bore with the correct selection of keys for each note, become amplified into warm, dark, sumptuous sound waves, and gracefully round itself as it resonates through the bell. With an unresponsive reed, one that is too hard to vibrate naturally or too soft to hold its shape under embouchure pressure, the sound is, well, lousy. Quacky, like a duck, which is what beginner oboists are often accused of sounding like.

So, there are a few things going on that an oboist has to control: the quality of the instrument; good habits with regard to embouchure, breath control, and fingering of keys; and using an excellent reed.

It’s not too hard to acquire a good instrument, although they are expensive! I happen to own a wonderful Violetwood oboe that plays like a dream. However: Embouchure, breath, and fingering control are built and maintained by quality instruction in technique, and you guessed it: tons of practising those techniques!

That leaves the bane of all oboists: the reed. It’s really hard to make or buy a perfect oboe reed. Making them requires good tubes of cane, and then gouging them to the right thinness, and then assembling and scraping the blades down, but not too much….You can buy a really good one, but it will still need your expertise to perfect it. The oboist will still need to have a good well-sharpened reed knife to whittle away on it, correctly, testing it at each slight scraping away of the cane until it feels and sounds perfect.

My teachers always emphasized the primary directive of adjusting the reed to the player, and not vice versa. Settling for a bad reed, one that is not responsive, or plays too flat or too sharp, means monkeying around with your breathing, posture, embouchure, fingering, in order to get a decent sound out of it. In other words: the reed is controlling you.

In the process of doing all these contortions, to the point of losing all your hard-earned good technique, you are no longer making your music. You are relinquishing your unique identity and timbre of sound, your signature as a musician, in order to produce instead an adequate sound, from a poorly crafted piece of cane. Your ability to play as a unique and expressive musician and muse of the instrument are the cost of this battle for control of the instrument. Convenience has won out.

Again, back to my wineglass-waving relative. “Why would anyone want to do something hard if they don’t have to?”

Making reeds is hard! Making excellent reeds is even harder! But, as musicians, driving to capture the correct sound for who we each are, it is imperative to strive to make them. Or else, we are lost to a poorer quality sound of convenience.

Just like the oboist, we must patiently and attentively whittle at those rough places. The easier ways out – of letting the reed, or the situation, or that other person, control you – will cost you your self-hood.

I recently received an email advertising a master class in learning how to adapt to and play with low quality reeds. Imagine! The premise is: that bad reeds abound. They come from making them without enough expertise or good materials; or else we buy them, and are unable to finish them well. Either way, this reed hack master class will teach you how to distort and bend your good habits and technique in order to play low quality reeds.

I immediately thought of my teachers, often correcting me for doing just that: trying to get a good sound out of a bad reed, thus sacrificing the hours and hours of hard work I’d done to develop good technique in the process. Those reeds, they said, needed to be either adjusted or replaced.

Looking at this past year now, and the unknowable that will unfold ahead, how will you adjust your reeds? will you adjust yourself further and further to meet the needs of reeds or situations that are unsuitable? or take the opportunity this time of year sets aside and do the satisfying work of refining these situations and yourself, forming lovely reeds for playing your song?

I wish you all a year of good music, for yourself and with others, and all the joy and connections that music brings your way.