-

Genmaicha

This morning, perhaps being distracted by the panoramic view westward of sunrise hazels, purples and shimmer of highrise windows reflected onto urban canopy of trees, I dropped my favourite jar of Genmaicha, spilling a good portion onto my kitchen floor. “Oh, dear” I said, then saw with relief that the jar, a diamond patterned glass cylinder with a knob top, had not shattered on the kitchen’s new laminate flooring. I wasn’t sure whether the tea in the jar, or the jar itself, was the more precious.

The jar was a treasure found in the ‘Bargain Barn’ during my first few days living in the desert a few years ago. I was outfitting my coach-home’s galley-sized kitchen and needed some containers for teas and larger spice items, such as cinnamon sticks. I loved the Bargain Barn, the town’s treasure trove for items that were perfect for outfitting a desert home, left behind by those who had moved back into modern, conventional, city living. Most items were anachronisms, having been recycled into new homes many times over the decades.

This particular jar was a doppelganger for the one that had lined our kitchen countertop when I was a little girl, back in the ’50’s and ’60’s. Along with the kitschy cat plate that came with the coach, it always brought up fond memories of my mother, in her bright apron with the orange and blue ruffles, busy in the kitchen, with little me following her every move, chattering away with nonsense about what the cat was thinking or doing, and could I have a carrot, please?

These memories informed me as I selected this jar from amongst several off the shelf at the Barn. Now, what would go into it? Sugar? Cinnamon sticks? Ground Cumin or Turmeric? Or, just leave it clear and set it on the sill of the sunny kitchen window where its lacework of facets could catch the light and reflections of the trees and hummingbird feeders? I took it home to ponder.

A week or so later, I drove to a mountain town high above, but not far from, my desert home. The town centre is charming, kept in an old timey sort of way for tourists and vacationers, but mostly to supply the locals with their more rustic needs. The patchwork of shops sold ceramics, handspun wool and weaving, mountaineering and ski equipment, ice cream, candy stands, bakeries, bistros, coffee shops, a restaurant, and some exotic imports stores.

Up a flight of stairs in the centre square’s red wooden feature building, there were a few quieter shops selling Amish farm goods, wool for knitting, and an oriental imports shop. I wandered into the oriental imports shop.

It had been quite a while since I’d seen anything Asian, and I now realized how much I missed the almost ubiquitous presence of Asian culture and people back home in Vancouver, Canada. It had been my custom for decades to go to the traditional Chinatown near downtown Vancouver and shop for produce, herbs, Tai Chi clothing, shoes, swords, kitchenware, and just enjoy a day off from the suburbs, as well as attending weekly rehearsals with the Chinese orchestra and choir; now this shop reminded me of all those things that were part of where I had been.

What to buy? or to just look and take in the musty scents and pastel and black colours of kites and clothing and toys and cosmetics and toiletries. What I wanted most was tea; either Oolong or Genmaicha. Tucked away next to some brightly coloured packages of cosmetics was the tea, and I picked a lovely tin of Oolong tea and a box of Genmaicha. The proprietor nodded as she checked out the items and I realized how calm and soft everything had been in that store, even in comparison with the little mountain village, which had a hustle about it, directed at tourists to buy goods and eat goodies.

Genmaicha tea is a blend of bancha green tea and roasted brown rice. It has a nutty, slightly sweet flavor and a yellowish color; it is a popular drink in Japan. Sometimes it is called ‘Popcorn Tea’ because the toasted rice kernels look like small popcorns mixed in with the green tea leaves. Some days, for feeling a warm glow, I put a few leaves of Oolong tea into a pot of boiled water, but other days, I just want to sip and taste the toastiness of rice mixed in with a gentler flavour of green tea; sitting with genmaicha is an oasis of warmth, aroma and flavour and an excuse to rest on a busy day or lazy morning.

So, this morning, that is what I wanted: to have a toasty beverage and sit and ponder the view over the treetops outside my windows. But, alas! as I grabbed the precious latticework genmaicha-filled jar, it slipped out of my fingers and crashed to the floor, much of its contents spewn out like lava from a volcano. I could smell the toast-and-tea odour as the first indicator that the tea had spilled. The words, this is all correct went through my mind as I gazed, confused, at the floor. There appeared to my eyes to be a mess of spilled, precious tea leaves and rice. But, my reflexive action was to understand it as nothing was amiss here.

I was surprised at how my reaction was not one of disappointment or loss or grieving for having damaged something so precious to me. My reaction was elsewhere, on how all things are integrated into a whole, and that there is movement forward, even in loss, no matter how great, or small.

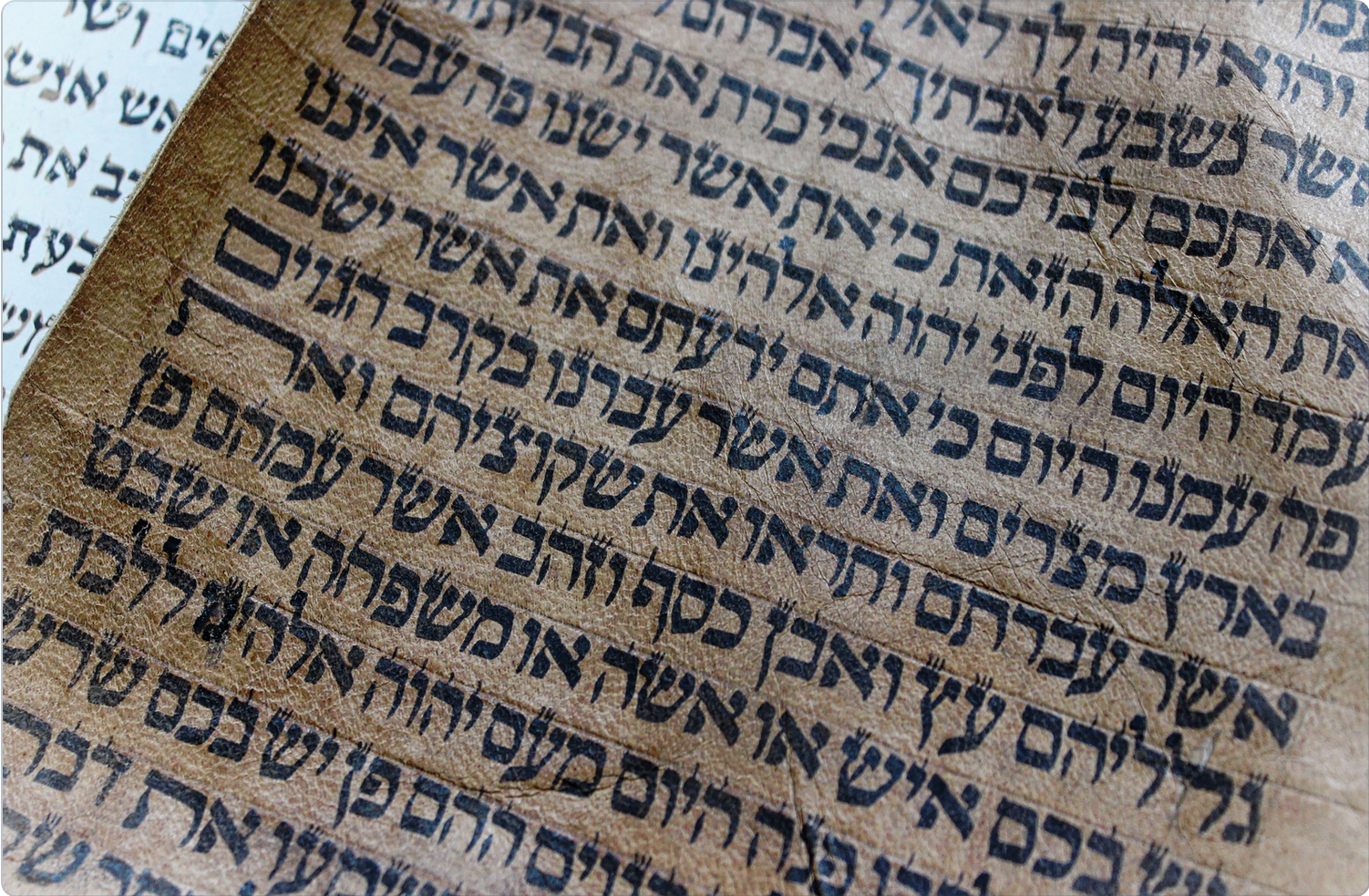

Putting this into perspective, no one died. Yet, if there had been a death of a loved one, the first words I would have uttered as a Jew, are: Baruch Dayan HaEmet, God is the True Judge, or Judge of Truth. Either way, we are saying that things happen, and that even in loss, there is an Ineffable Presence that will always be there and hold us dear. This morning, it was a simpler version of this belief in the inevitable and unceasing flow of circumstances: accepting that all that occurs reveals and allows for something new.

I saw, not the loss of my precious tea, or myself as clumsy and bearing blame for the loss, or my becoming old and losing capacity for self-care. What I saw was that some tea had spilled, and that it was time for that tea to spill. I had been so endeared to the precious memories evoked by the jar and idea of enjoying the tea, that it had stayed in the jar, untouched, for far too long: In fact, it was going stale because of my reluctance to use any of it.*

I felt grateful for this early morning wake up: a wake up reminder that change never ceases, and that our ability to appreciate change as growth, makes us more at peace with whatever we may encounter.

*Later on, I read that in 19th century England it was considered good luck to spill tea leaves https://twinings.co.uk/blogs/news/tea-superstitions

-

Narrow Bridges and Narrow Places

The 50 days between Passover and Shavuoth mark are a time set aside to mark the Biblical journey of the Hebrew people from Enslavement in Egypt to Revelation at Mt. Sinai. Egypt is called Mitzrayim in Hebrew, meaning ‘narrow place’. This year, the retelling of the journey of my ancestors from out of the Narrow Place of bondage to receiving the Torah (Law), brought to mind a saying of Rabbi Nachman of Bratslav, ‘“The whole world is a very narrow bridge; the important thing is not to be afraid.”

This year has been a turbulent one worldwide. There are refugees streaming away from crises in their homeland, there are reversals of progressive gender equality legislation, there are demands by college students to be provided with a safe environment, terrorism is on the rise, and at least one American Presidential candidate is running on a platform of backlash against any progressive racial, cultural or gender policies. What is driving this? Fear.

Fear from all quarters is headlining the news these days. People are afraid. Some are afraid of losing their familiar way of life, some of losing their long battle for hard-won rights; some are expecting their path to be free of obstacles, others are creating obstacles to draw attention.

It seems they are all walking across narrow bridges, or wandering lost in the desert, while schlepping (carrying) along their old fears.

In the case of the Exodus story, as soon as there was any hardship in the desert, the people demanded to go back to the Narrow Place of Egypt where things were familiar, where they even fantasized they had dined on fish and leeks.

In the case of the Exodus story, as soon as there was any hardship in the desert, the people demanded to go back to the Narrow Place of Egypt where things were familiar, where they even fantasized they had dined on fish and leeks.The wandering in the desert was scary; the best thing to do was blame someone, Moses their leader, for their scary predicament. It was much like crossing a narrow bridge: you are in an unrecognizable place, neither here nor there and can only go forward.

Fear of changes such as these arise in part due to a lack of structure or guidebook. The Hebrews escaped the Narrow Place knowing only that 400 years of slavery was enough, and they could not stand being slaves any longer.

They did not know where they were going; and that was scary. The narrow bridge they were crossing was certainly taking them away from a very bad place. If they could endure the chaos that resulted from a new and unfamiliar freedom things would certainly be better. They did not have a structure for this mass exodus; instead they just had to stay the course and keep walking, fear and all.

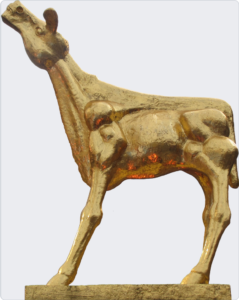

After many mishaps and building their own source of guidance with the Golden Calf, they received the Torah at Mt. Sinai. I like this Biblical example of how treacherous it is to cross from places of chaos into those of order. I believe the model can be applied to ease our modern maelstrom of push-and-shove to create novel cultural, racial and gender paradigms rather than see what has already been bequeathed to us by our ancestors.

I will share a recent personal experience. I was walking home from synagogue one Shabbat. As I passed the outdoor patio of a coffee house, I overheard a very loud conversation that was overtly using expletives against both Israel and Jews. I thought about what to do about this rather brash conversation and decided to turn the situation into an opportunity to ask what the basis was for the loud and offending remarks. First, I approached the loud group of young people seated at a table and simply identified myself as one of the Jews they were deriding. As I walked away, the young people beckoned me to stay and speak with them.

Through these actions, we all set aside fear and embarked upon a walk over that narrow bridge together.

Through these actions, we all set aside fear and embarked upon a walk over that narrow bridge together. We talked. When asked, they could not provide any facts about Jews and Israel; they only knew their negative views from friends’ opinions and the abundance of left-wing popup news media on the street. They wanted me to give an overview of Judaism and I gave them some dates for important events in the formation of the modern country of Israel. I invited them to Google these and see what else they could learn.

We talked. When asked, they could not provide any facts about Jews and Israel; they only knew their negative views from friends’ opinions and the abundance of left-wing popup news media on the street. They wanted me to give an overview of Judaism and I gave them some dates for important events in the formation of the modern country of Israel. I invited them to Google these and see what else they could learn.Contrary to what fear might have said about this conversation, they thanked me profusely.

By taking those steps toward them a journey began, away from the enslaving ideas we had on both sides, toward a way of understanding how this chaos of anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism came to be.

I also learned that diplomacy happens in direct 1:1 conversations: not through online polemics, international political gestures, grandiose political swaggering, or biased news media.

I have told this story about the coffee house conversation to others. Usually the first response is, with all that pressure to conform to the status quo of the neighbourhood, wasn’t I afraid to approach these young people? My reply has been that my only fear was that because I was peacefully walking home from synagogue when I overheard them, I might be violating Shabbat (the Sabbath) by potentially creating a conflict. However, the wisdom of faith told me that the honest way to create and perpetuate Shabbat peace was to take that walk on that narrow bridge and engage these people, without fear.

We observe the passage of 50 days from Passover to Shavuoth as an opportunity to take steps away from things that we are unsafely bonded to and find an order in our lives that matters.

There are still a few days left before Shavuouth begins, on the evening of June 11th. Find time over these days to leave behind something that holds you back—a habit, an addiction, a prejudice, a hurt—and move ahead with faith rather than fear, that something good lies ahead.

-

Visiting the Sick, Knowing the Self

Last week I had a series of dreams that I could not remember any details of, except that they all had a dog in them…It is unusual for me to not have recall after I awaken. I have a practice of recalling my dreams, where I find wonderful insights into my motivations and how to approach decisions that await me when I am awake.

One of the dogs that came to me is my dog Carlea, who was my companion, conscience, and escort in my many activities and adventures for her first four years of puppyhood and adolescence. When I moved to New York 18 months ago, I knew was not the place for her; she had grown up in rural Saskatchewan and Vancouver, so it was out of the question to bring her into metropolitan Manhattan to be an apartment dog while I ran all over the City taking voice and music lessons, going to seminary, and chaplaining at hospitals. She still visits me sometimes, just a brief breeze of picture memory, and sometimes, like last week, she comes and lays her soft head and long muzzle on my belly while I sleep, my arm wrapped over her silky-bony frame. Maybe she was called because I had felt troubled by some looming decisions that were not yet fully in my awareness and would appear later in the week. Her presence was reassuring and loving.

If someone were to ask me to describe what pastoral care is, or Bikkur Holim visiting the sick, or being a chaplain, that is how I would answer. Being a reassuring and loving presence, someone who comes, unbidden, to be a comfort and witness when someone feels disconnected or alone.

Our human quest to domesticate everything, including the medicalization of illness, how to be sick and how to visit someone who is sick, has necessitated the development of guidelines. We seem to have lost the natural instincts for what to do. Thankfully, our various ethnic traditions have preserved much of that indigenous wisdom we once had. Our traditions can offer us many tips for being a good visitor: things to say; and also things not to say –my teacher Rabbi Simkha Weintraub would call these, ‘unintended curses’ ; we have advice on how to offer help; we have the Jewish book of rules, the Kitzer Shulchan Aruch gives us strict details such as when to visit, where to sit or stand, what times of day not to visit, and more. The bottom line though, is to come, like Carlea: as yourself, yet without any agendas.

This isn’t so easy as its simplicity suggests: we all want to be helpful, and what is helpful can be hard to figure out on your own. In fact, if you do try to figure this out on your own, you’ll be missing the input of the person who is ailing: ask them what they want, otherwise, you are likely only serving your purposes and not theirs. Here are some examples of what people who are sick tell us, in a survey compiled by Rabbi Weintraub:

This isn’t so easy as its simplicity suggests: we all want to be helpful, and what is helpful can be hard to figure out on your own. In fact, if you do try to figure this out on your own, you’ll be missing the input of the person who is ailing: ask them what they want, otherwise, you are likely only serving your purposes and not theirs. Here are some examples of what people who are sick tell us, in a survey compiled by Rabbi Weintraub:“Ask me, don’t exclude me or make assumptions about what I need”

“Listen. Don’t try to make ‘it’ better before you know what ‘it’ is”

“Don’t staunch tears. Don’t be afraid of tears or rage; respect them”

“Teach me how to pray—not just ‘nice’ prayers, but prayers that rise out of my rage, my loss, my paralysis”

“End the silence. Bring illness out into the open”

How is it that we have become so detached from someone who is ill that we suddenly start making assumptions about what they want, try to keep everything light, cover up the depth of their illness?

There have been many answers, and bearing in mind that we have all been sick at some time in our lives, it is not a foreign land or unexplored territory for anyone. What is happening then, is that the sick person becomes a mirror that reflects our own mortality, or ‘there but for fortune go you or I”. We want to be close and helpful, yet at the same time we keep our distance or create false lightness as a barrier to accessing our inner fears and discomfort about illness or death.

But, that’s okay, we all have that reaction. And, there are ways to be present without raising the shields that disallow the sick person their need for your company and companioning attention. The best solution is to know yourself. Be aware of what your needs are, and stay tuned to what the care recipient is asking from you.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

In Native American tradition, Dog Medicine asks you to understand how much your sense of loyalty or convictions to offer care, are overturned by your need for approval or keeping things safe and comfy for you and others looking in on the situation.

The modern practices of Spiritual Health Care do, too. The following questions are guides for you, taken from the shared wisdom of past and present. They offer ways to ask yourself how well you are tracking yourself while you care for someone else:

- Have I recently forgotten that I owe my allegiance to my personal truth, or am I seeking external gratification when I help someone?

- Is it possible that gossip or the opinions of others have jaded my loyalty to a sick friend?

- Have I denied or ignored someone who is trying to be my loyal friend when I am ill?

- Have I been loyal and true to my goals to be present for people in need on their terms?

The double Torah portion this week, Behar-Bechukotai, concludes with instructions for how to care for those who find themselves in times of need, widows, orphans, indentured servants.

As always, we are reminded to treat them as members of one’s own household, and to remember that we were once slaves in Egypt. What does this tell us? To not lose that God connection, the one that reminds us that because we may be in good straits now, that can change at any moment, and the person you are taking in, could one day be you.

Along these lines, there is a saying amongst the community of people with disabilities: they call the rest of us CRABs, “Currently Regarded as Able Bodied”.

Along these lines, there is a saying amongst the community of people with disabilities: they call the rest of us CRABs, “Currently Regarded as Able Bodied”.In an instant, such as an accident or the recent bombing at the Boston Marathon, your healthy bodily capacities can be gone, and you will find yourself depending upon others as never before.

In Judaism, we have the Torah to tell us how to respectfully engage people in need, bearing in mind that we were once in their shoes.

And modern Spiritual Health Care practice tells us how to look inside and know who we are before, and as we are, offering help.

May we be blessed with remembering our capacities to truly who we are, as we companion with and help others.

This Sunday, May 5th 2013, from 1-3pm I will be leading a further discussion of Jewish and Modern Traditions for Visiting the Sick at Or Shalom Synagogue in Vancouver.