-

If Moses Used A.I.

This week’s Torah portion is called Ki Tavo, named from the opening words of the reading, which mean, “When you enter”. In this section of the Torah, from the Book of Deuteronomy, Moses is continuing his summary to the Israelites of how they are to be, as new inhabitants of the land which God had promised them as their inheritance.

The speech is eloquent, at least the the words that have been passed down to us which are attributed to Moses are. But, also recall, that much earlier, in Exodus 4:10, we read that Moses is not so eloquent of speech,

“Moshe said to YHWH:

Please, my Lord,

no man of words am I,

not from yesterday, not from the day-before, not [even] since you have spoken to your servant,

for heavy of mouth and heavy of tongue am I!”*God’s anger flares, and He reminds Moses who created humans and their abilities in the first place. After more assertions from Moses that he cannot speak well, God points to his brother Aaron, and tells Moses,

“You shall speak to him,

you shall put the words in his mouth!

I myself will be with your mouth and with his mouth,

and will instruct you [both] as to what you shall do.”* text quotes: The Schocken Bible, Everett Fox, 1995This dialogue caused me to think about AI. While recovering from the exertions of my trip to Taiwan (you may have noticed in the photos of the previous post how bloated I became there), I have been watching a lot of TV. I like retro TV shows the best.

On one particular streaming station, almost all of the commercials are promoting an A.I. writing assistance app. Over and over again, my resting brain took in the peppy and chipper rolling out of all the amazing tasks this app can do: for you, for your business, for your teamwork.

As a writer and writing educator, though, I took offence to this shortcut tool, seeing it as just another ‘hack’ to enable people to shortcut and bypass using our brains’ own sublime social and technical capabilities. AI can certainly be a communication boon or even lifeline to those who have learning and developmental disabilities. Going to school provides an opportunity to work hard and develop strong social and communication skills, allowing us to not only communicate well at work, but also become independent and capable adults socially.

I watched the commercials with trepidation. In one version, three young women sat in a room, and one of them had an idea for a product to manufacture and market; we saw her computer’s text bubble to her team about it. Her colleagues, though, were writing text bubble responses with phrases and words that were cutting and crude: “You’ll have to fix that container, it won’t work.” Certainly not what any high school or MBA educator would have approved of!

But, thankfully, our commercial showed us how these teamsters could tell the AI app to make their phrases more friendly or supportive, even choosing the wording a gradient of softer or harder wording. In the last scene, the original brainstormer is opening a box with her original idea product, now gone to market, thanks to the wonderful, supportive messages from her development team.

Well, at least these colleagues recognized that their terse inner thoughts and outgoing phraseology were out of place for work. These were okay for an after-hours dish-session about their esteemed colleague, but not okay for getting the work done. With the aid of the AI app, though, they bypassed their real, dishy, thoughts and let a robot fix it for them. Sort of like the butler Jeeves getting his master Wooster out of yet another malaprop faux pas. But, I wondered, what happens when they have to meet face-to-face, say, around a conference table; or meet with clients to demonstrate their product line and have a live conversation? Where will the AI app be then?

There is always a risk involved when communicating information second- or third-hand. Suppose God handed Moses the AI app to get the job done, instead of pairing him up with his brother Aaron?

Let’s look at the difference:

AI

- Artificial intelligence

- Words generated by algorithm

- Grammar and etiquette rules

- Incapable of empathy

- Has no agendas or purpose

Aaron

- Human intelligence

- Words provided by Moses to Aaron

- Divine inspiration

- In loving, supportive relationship

- Has inspired purpose and intentions

I could go on with these comparisons between contracting to communicate with AI vs Moses enlisting his brother Aaron to speak to the Israelites, but this list has the essential points on it.

Think about what the most important job is for a Prophet: Leader of the People? Rule-maker? Rule Enforcer? Soothsayer? Seer? Smiter of Sinners?

My answer: Above all else, a Prophet is a Role Model. Yes, A Role Model. This is the person who models not what the directives are for the people; but also how to be a person. We sometimes make excuses for ourselves when we miss the mark, and say, “Well, I’m no Moses, after all…” but actually, Moses was an imperfect, flawed person. We just read about his speech impediment.

But, also, he had a very real human personality. He got angry, a lot. Angry with the slave master who beat the Hebrew slaves, with the stubborn Israelites who complained and built the golden calf, and he got angry with God. He was a workaholic, trying to manage the people all by himself, until his father-in-law Jethro told him to delegate his onerous amount of work and appoint judges to offload much of it.

Perhaps your ideas about what a role model is are shifting now. If Moses wasn’t a perfect person, who can we look to!? AI?

Despite being imperfect, Moses was a person, chosen because he had vision and tenacity, and the compassion and strength to take risks to see that his very human sensibilities about right and wrong were fulfilled. When God wanted to destroy the Israelites, Moses interceded (Ex. 32-11). His arguments with God are noted several times. He was fearless in bringing forth his beliefs and willing to negotiate to move things forward.

When it was time to enter the Promised Land, though, Moses was not allowed to enter. Why would this exceptional human being and role model not be allowed to continue on with his inspired leadership? because his mission, to single-mindedly bring the Israelites to the new land, had ended. And, as an exceptional human being and role model, he understood what defined his purpose.

Instead of covering himself with sack cloth and moaning, or berating God, or taking out his anger by harming innocent others or himself, Moses chose to close his relationship with his people by giving them the eloquent and soul-touching Deuteronomic charge and last instructions as they were about to enter the Promised Land.

This is what we learn from our role models: how to live by our truth and vision, no matter who we are; and how to accept closure and find peace at the end.

Tell me, would the words from an A.I. app inspire you this way?

-

Cultural Integrity, Valuing Heritage

“Make new friends/but keep the old; one is silver/and the other’s gold”

We used to sing that tune many years ago, usually during the closing campfire the night before a long bus ride home to suburbia from Girl Scout camp. After two weeks of camping and learning together in the great outdoors, sleeping under the stars in outdoor bunks, tending the horse corrals, swimming at the poolhouse, and singing lots of songs. The mundane chores of divvying up food servers, dish washers, and flag duty guards were done by song; routines that became old friends. These rituals helped us retain a sense of order and familiarity, of how to share chores, the fun of learning with others, and the special songs we sang about how to do this, lingered even after we returned home.

Music does that. Some music is new, some is old. Our songs came from around the world: Maori, French, Native American, British, American folksongs, to name a few. The music embeds a sense of time and place and important relationships into memory.

Sometimes, though, older music or traditions are replaced; or worse, discarded. Time and distance can cause alienation from cultural treasures, especially if the chain of connection is broken. from the origin. We learned the value of keeping our older friends or traditions, while adding new ones, from the song, “Make New Friends, But Keep the Old”.

I want to share that belief with you today through a recent experience of mine, travelling to Taiwan with a group of Canadian musicians, to rehearse and learn with a local orchestra in Taipei. It was quite a long distance to travel! But the truth is, it is quite one thing to play music from a score thousands of miles from where the music originated, and quite another to be locally and culturally immersed and learn the context and full authentic sound of the music. This is what we did.

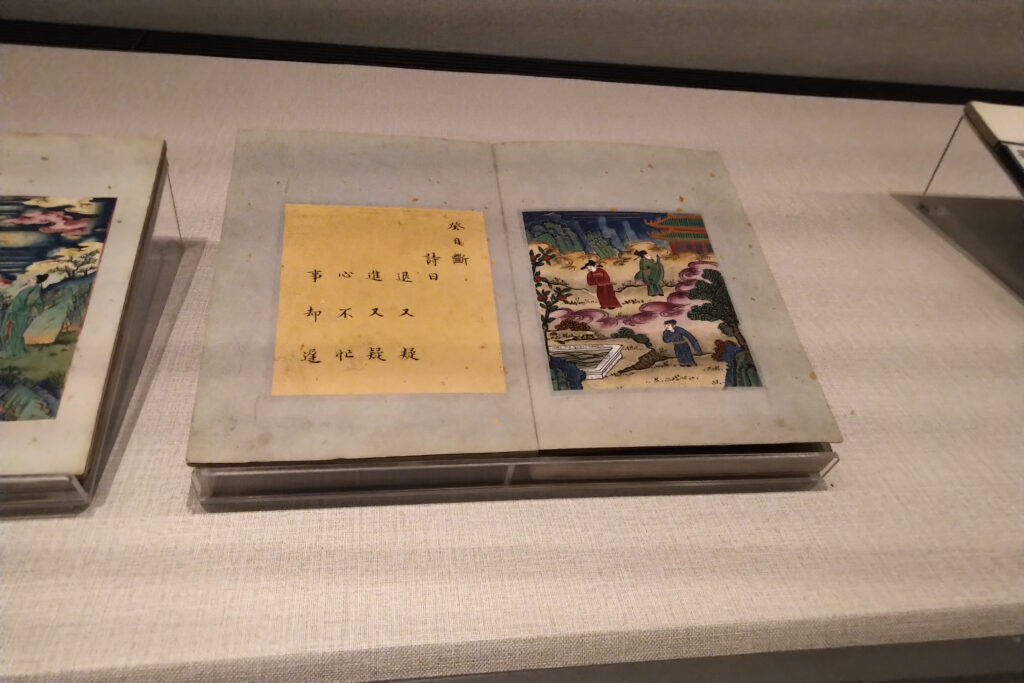

We arrived at 5am local time, after 20 hours of travel, and after a brief stop in our hotel rooms, met for breakfast with our host, Dr. Chen Zhisheng. Then headed for the National Palace Museum.

It seemed crazy to me, with part of my mind or neshama still in Canada, to be rushing off to a museum within hours of landing. I like museums, but couldn’t we have a nap first or something? But, there was reason for Dr. Chen’s suggestion we go there: tradition and culture. That is what we came to Taiwan to absorb, to bring into our music. And, so into the museum we went.

We mostly looked at the excellent collection of foundational manuscripts there. My favourites were pages from treatises on the Yi Qing (I Ching).

Some TCO members took part in master classes in conducting for Chinese orchestra. I had Suona lessons, particularly reed-making lessons, as it is not possible to buy ready made alto suona reeds. My teacher, “Daniel” 林瑞斌 Lin Ruibin, came to my hotel each morning and so generously and graciously made reeds and gave me tools as well as lessons on my instrument and information on where to buy supplies.

We started having orchestra rehearsals after a few days. Because of the great size of the orchestra, we had to move the rehearsal venue to the dance/gym building at a school in Taipei.

Rehearsals kept up daily, and so did the post-rehearsal food! One evening, Dr. Chen took us all out to a 22 course Japanese dinner. Another night we went for Izakawa, so loud and fun and raucous, with great beer and cool A/C.

cat chilling on roof by the sea We continued our cultural explorations, going to night markets and shopping for gifts and personal treasures in the retail stores. I bought Chinese preschoolers’ calligraphy books and stationery, a dress, toiletries.

Food is a big part of Taiwan’s culture, a mix of Chinese, Japanese, Thai, and other Asian cuisines. Prices are so low and quality is so good, and everything is fresh.

In all of this hubbub, though, I truly appreciated starting my day with a quiet breakfast and looking out the window of my hotel’s breakfast room.

Eventually, the day came for our concert, Thursday 20 July. We’d had our private music lessons, orchestra rehearsals, and dipped deeply into Chinese history, language, music, food, landscapes, and customs over the past ten days.

The National Concert Hall was filled, both orchestra level and balcony. Everything went like clockwork. Most notable for me was how smooth and blended movement and sound were; my experience was that it just flowed. There was none of the usual anxiety about missing cues or entrances or playing off key as with bands and orchestras where we played well from scores, but were mostly lacking cultural literacy for the music. Instead, there was a naturalness and understanding of what we played, and we played together as a corps rather than sweating out individual parts.

All in All, it was a delightful experience, and the intent to share traditional cultural context for this music with Canadians came back home with me. Although there is motion in some parts of Asia to replace traditional Chinese music with Western orchestral music and instrumentation, and emphasize soloists, preserving the beauty and transcendence of the culture as a whole and sharing it with those in diaspora is Wisdom at work. Yes, modern western instruments were integrated into the orchestra, and yes, some pieces were very modern in vibe: however, these were enhancements of traditional sounds, tonalities, and instruments.

The Xianse Gong Chinese Orchestra and we Canadians made new friends, and we will depart to share with our golden friends back home, extending the reach of traditional Taiwanese culture and music, for the benefit of all.

-

Are You Lonely?

The U.S. Surgeon General states that loneliness is now in epidemic proportions. News about high levels of loneliness is found in sources globally, including Harvard Magazine and Al Arabiya. Is loneliness a new thing, since the rise of COVID-19, and is if affecting you?

Loneliness is not a new phenomenon, it arose with the first life forms, since time immemorial. I suspect, in fact, that the even the earliest life forms had sensations of loneliness.

For example broadly, the lone survivors after their primordial soup desiccated under the unfiltered sunlight, or catastrophic flood or volcanic eruption. Or, perhaps the simple lack of contact stimulus set them moving about to find mates in order to procreate or assist with feeding.

Of course, we can only speculate on this, although in an informed way. I was delighted to find a book that allowed me to integrate my personae as both Biologist and Chaplain, Origin of Group Identity by Luis P. Villarreal. This book discusses the importance of group identity for all organisms, even ones that seem inanimate, such as viruses.

Moving forward a few billion years, though, not much has changed for living organisms. We all become alone, from the single-celled organism to the very complex human being. Transforming and then defining this state of singularity into the cognate of ‘loneliness’ shifts what is natural and common into a status requiring action.

As humans, endowed with the ability to manipulate our environment, we can do things, such as gather and live together in communities, share resources, such as hospitals, places of worship, governance, and recreation. This adapting the environment to suit us rather than vice versa, where the environment makes the rules and the organism must adapt, is something that sets us apart from how other life forms address solitude.

Of late, we also have social media. That can be a good thing. For people who are housebound due to illness- or age-related frailties, social media can be a life-line for drawing in necessities, such as companionship, grocery delivery, or a doctor visit.

But, over the past few short decades, relatively healthy cohorts have drifted away from shores of direct personal contact towards the uncharted lands of the solitary individual touching others via their electronic keyboards: much of value has been left behind. The tips of the icebergs on these man-made seas has been of concern for quite some time now: cyber bullying and the emotional impact of social media on adolescents, the ability to post anything and everything with strokes on one’s inert, faceless keyboard. And now, we have AI fabricating ‘facts’ about ourselves and others.

For now, I want to focus on loneliness because that is what the world’s esteemed authorities on human health and welfare are telling us we are suffering from, in pandemic proportions.

I’ve already given hints as to the scientific/biological origins of ‘loneliness’. Now, let’s look at what our wise and compassionate human ancestors gave us through their legacy of wisdom, of Torah, regarding what loneliness is and how to take care of it. This week’s Torah portion, Eikev, in part addresses speaks of loneliness, through the speech of Moses in Deut. 10: 16-19:

“(16) Cut away, therefore, the thickening about your hearts and stiffen your necks no more.

(17) For your God is God supreme and Lord supreme, the great, the mighty, and the awesome God, who shows no favor and takes no bribe,

(18) but upholds the cause of the fatherless and the widow, and befriends the stranger, providing food and clothing.—

(19) You too must befriend the stranger, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt.”

The definition of the Hebrew word for Egypt, mitzrayim means a place of narrows: the narrow place wherein the Israelites were squeezed, through their enslavement. These words of Moses are so relevant today that they could have been written recently: about living through the COVID pandemic, with their reference to us all having been strangers in the land of Egypt/Narrowness at one time or another.

Indeed, anyone over the age of a few weeks old has lived through some or all of the pandemic, that strange and uncertain time of travelling through some harrowing and narrow bridge or birthing canal into a new land. Think about what you did during that time. We had to isolate, stay home, stay apart from others. We had to make sacrifices and take care of ourselves as individuals, even if we lived with others, because there was no place to go, no distractions such as going to the office or shopping, or to a movie or a vacation. We had to be individuals navigating enforced tight quarters and relationships, or as isolated individuals.

Creating and maintaining personal boundaries is an important skill: however, the lengthy periods of COVID isolation enforcing them, combined with replacing direct personal contact with social media, may have created thick walls of impermeability where once we absorbed the presence of others, and could feel empathy and normal social awareness. This is a thickening about the heart, just as described in verse 16 above.

The stiffening of the neck is what we do when we know what is right but refuse to do it. The child who won’t eat their vegetables or pick up their toys, the adult who acts on impulse to their detriment; or those of us ignoring calls for empathy, contact, or love from others because it’s just easier to send a text or emoji.

Ask yourself, “have I built a great callous around my heart?” are you able to have real and safe interactions with others, away from social media?

Pick up the telephone and call a friend you haven’t spoken to in a while, or who has been away from usual activities due to illness or travel. Send a card, buy a gift, have a coffee.

Loneliness can cause us to assume others have left, moved on, or worse, are never coming back. Let them know you are here, too – that you are no longer strangers in a strange land.

-

Violence and Passive Aggression: The ‘Love Bomb’

I was making an inventory of the things I want to bring on my upcoming trip to Taiwan, where I’ll be performing with the Xianse Gong Chinese Orchestra. I’m very excited about this trip, as there will a few ‘firsts’ for me: my first travel away from Toronto since March of 2020, and also my first trip to East Asia. I’m going with a group, many of whom also play in the Toronto Chinese Orchestra. Here is a link to our concert, scheduled for 20 July: “On the Other Side of the Rainbow is Home”

High on the list, next to my Alto Suona, are the Tai Chi Chu’an slippers that I wear for morning outdoor practice. I’m hoping to join a group in the mornings at a nearby park while I’m there.

I looked at my collection of Tai Chi swords and sabres, wistfully. Much as I’d like to get extra practice with them in Taiwan, they are just too long and awkward to bring on a 13 day trip.

Then, another thought came to me, a memory of a conversation with someone who came to visit me while I was recovering from surgery a few months ago.

She was perusing my collection of books and artwork, then stopped. “Oh, you have weapons“.

“Where?” I asked. I followed her line of gaze upwards and towards a rack on top of the large keepsake display case in my dining room. “Those swords on that rack are for Tai Chi, they’re not for fighting or hurting people.”

Her nose scrunched upward, pursing in her lips as they did so, as if something smelled off. “I think of tai chi as something graceful and peaceful, not violent or aggressive, with weapons.”

“You’re right, it is graceful and peaceful. And also, Tai Chi Chu’an is a martial art – that is its origin, and if the martial applications and intentions of the movements are not understood or incorporated, than what is being done is merely arm and hand waving, with little benefit to health or inner strength.”

“That sounds violent.”

“Well, the whole point of learning Tai Chi Chu’an is to prevent violence. Tai Chi Chu’an is an internal martial art, designed to develop the inner self. By doing this, by reducing fear, violence can be prevented and if not, then the discipline and practice prepare one for self-defence. Inner peace, rather than external hard strength, is developed through learning how to engage with challenges, both inner and outer, with confidence and grace. It’s very psychological.” I thought this latter piece about psychology might register as a more acceptable reason for practising tai chi. But, her nose remained wrinkled as she continued to squint with distaste at the resting swords and sabre.

“I believe in Love Bombs as the best tool for violence prevention and self-defence”, my visitor said.

I’m not sure what a ‘Love Bomb’ is, and I asked her. The answer came as something about showing care of people and letting them know they are cared about.

Here is what I read about ‘Love Bombing’ online:

“You may have heard the term “love bombing” circulating online and on social media, but what does it mean? Although it might sound like something we’d all want — being showered with unlimited love and affection — it’s anything but healthy. Love bombing is a tactic often used by a narcissist to manipulate you into falling for them.”

This is what I came to understand while looking at my swords: Despite my being a functional invalid, with a plaster cast on my foot for the next several weeks, I never heard back from her or received the promised ‘Love Bomb’ of congregants or other helpers that were to come assist me while I recovered.

So, this irony raises some questions. What is the difference between violence, aggression, and passive aggression? and, how does Tai Chi Chu’an fit in to categories? Let’s start with the dictionary definitions of these terms, and proceed from there1:

- Violence: “the use of physical force so as to injure, abuse, damage, or destroy.”

- Aggression: “a forceful action or procedure (such as an unprovoked attack) especially when intended to dominate or master.”

- Passive-Aggression: “passive-aggressive behaviour, the donning of a mask of amiability that conceals raw antagonism toward one’s competitors, even one’s friends.— Hilary De Vries”

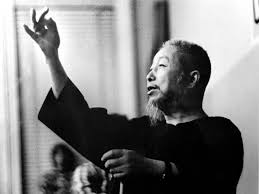

The history of modern Tai Chi Chu’an, of at least the past 100 years can be found online in a variety of places. Since my mind is on Taiwan right now, I found this quote in a lovely article in Taiwan Today about one of the founders of modern internal martial arts, Master Cheng Man-Ching:

“It is inconceivable to the uninitiated how a Tai Chi Chuan boxer trained only in physical and mental relaxation can fight a man of muscle. Relaxation is, in fact, the secret, and the degree of accomplishment is measured by one’s ability to relax. The most advanced achieve a mental calm that is a great force in itself.

Prof. Cheng often says that Tai Chi Chuan is a mental process that eliminates fear, which is man’s biggest enemy. Fear makes a man rigid, deprives him of flexibility and paralyzes both body and mind. When a student practices Tai Chi movements, he is taught to deal with an imaginary enemy who is strong and fierce. But when he is actually facing an opponent, he must imagine there is no one in front of him.

The appearance of Prof. Cheng as Tai Chi Chuan master is deceptive. He wears sideburns and whiskers. Chinese long gown and cloth-soled shoes are his everyday attire. On occasions, he puts on the gown-like dress he designed himself. He is more than unobtrusive; he looks sluggish….

During World War II, he staged two impressive demonstrations at the British Embassy and the American military mission in Chungking. In both cases, sturdy stalwarts experienced in Western boxing were selected to disprove his strength. None of their blows even landed. Instead of hitting him, they were sent lurching many feet away.

One towering giant of some 230 pounds tried twice. He was obviously perplexed by the inexplicable power of the small Chinese. Frustrated in the first attempt, he attacked even more violently. But force again undid him. He was tottering perilously toward a serious fall and the spectators were watching with apprehension. Before anyone knew what was happening Prof. Cheng had darted to his side to steady him with a soft hand on the elbow.”So, perhaps this story helps you have a more complete idea of what Tai Chi Chu’an is, and whether it is an aggressive, violent practice, as was my visitor’s belief, or a practice of letting go of fear and reducing aggressive behaviour.

In addition, I want to highlight the importance of understanding what ‘passive-aggression’ is. Sometimes people appear passive and harmless while they are actually harming you. The fear this behaviour arouses in you is blocking you from seeing the truth of what they are doing.

In these times we have so many restrictions on what one is or is not allowed to say. However, these restrictions do not change attitudes, and aggression and violence have not gone away. Instead, they are expressed in a sideways, socially acceptable, manner; such as a person making general statements about “certain people” or “those people” when they really are referring to you. We recognize this sort of covert violence and aggression in others as, “A Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing” or “A back-handed compliment”.

And we are harmed, because no one wants to be the little child who cries out, “The Emperor isn’t wearing any clothes”.

A “Love Bomb” is still a bomb.

Think about the people in your life, whether employers, family members, friends, neighbours, politicians, or anyone else. Are their behaviours congruent with their words? Are they helping you up or pulling you down with their polite conversation or when answering your request for assistance?

Violence and Aggression are overt and easy to discern. Passive-Aggression is much more difficult and covert. It seems too innocent, and socially unacceptable to call it out as harmful. The question arises then, of how to address the harm that aggression and violence does, whether overt or covert.

One answer is to become aware. As it is with Cheng Man-Ching: removing fear as your baseline allows you to fully feel and understand whatever is coming at you so you can address it in a non-violent and satisfying way. And, he reminds us, it takes work to be able to do this.

As I pack for Taiwan, and look ahead at practising Tai Chi Chu’an while there, a peaceful comfort comes with knowing that I am continuing to do my inner work, the work that helps me reduce fear and engage in my experiences with dignity and grace and confidence.

-

Beha’alotcha: Learning from Nature

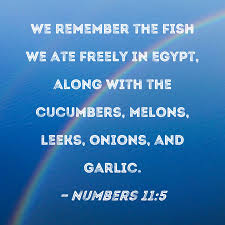

This week’s Torah reading is called Beha’alotcha, and in it, we read about the detailed and complex duties of the Levites. The Israelites are deeply in their desert sojourn away from the Narrow Place of Egypt, and we also read about a lot of complaining.

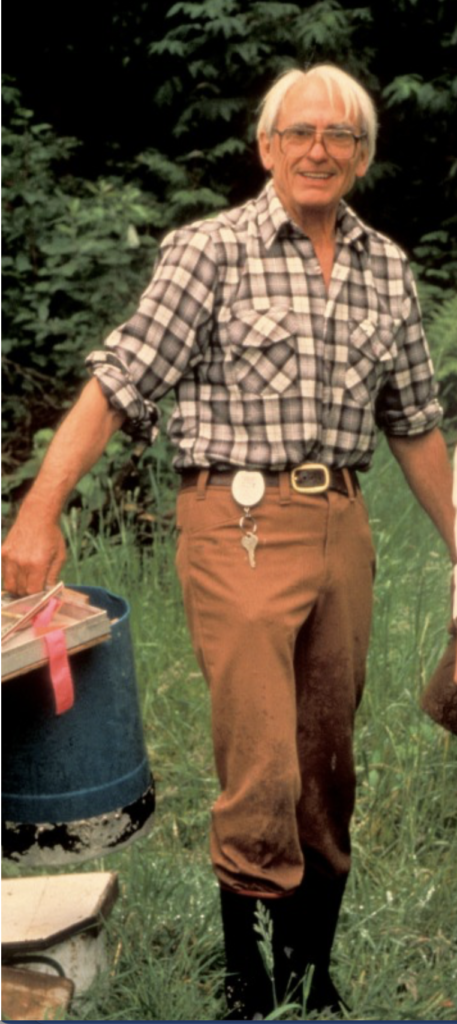

This prompted me to recall my days back when I was a Biologist, when I studied Population Biology and Genetics. My supervisor was a student of Dr. Charles Krebs, who had been a student of Dr. Dennis Chitty.

Dr. Chitty published research on the population fluctuations of meadow voles. Remember the Disney film, “White Wilderness”, where we watch the lemmings control their cyclical explosion population growth by jumping over cliffs? Well, that was Disney, and that portrayal was a hyperbole for what the voles, which are related to lemmings, would do when their numbers caused overcrowding and a scarcity of resources.

From his observations, Dr. Chitty proposed that cycles in wildlife numbers are self-generated by the interactions between individual animals. His conclusion, that changes in aggressive behaviour and physiology can prevent unlimited population growth, is now a fundamental tenet in population ecology. This is recognized as the ‘Chitty Hypothesis of Population Regulation’.

Dr. Chitty and his students were able to demonstrate in the lab and field that overcrowding these innocuous little mammals caused them to become extremely aggressive towards one another and overgraze on the plants and insects they fed on. That is how their population sizes come to fluctuate cyclically. They don’t need the drama of some mad-cow, deranged beeline for the nearest cliff or chasm to plunge into.

The truth is, population regulation is how Nature works. We as humans, have a Divine intelligence allowing us to create laboratory scenarios to explain what we see animals doing in the wild. The abilities we have for insight, to transfer what we learn from Nature to better ourselves, are gifts from God.

We differ from animals because we can look at our options and make choices about how we want to prevent ourselves from biting each other to death, or destroying all the food resources in our environment; and we can wear masks and make vaccines to control the spread of disease.

We don’t have to jump off a cliff when life becomes overwhelming, although these days so many people only see that option, emotionally, spiritually, or psychologically.

Perhaps we could have foreseen and done a better job of averting these global days of floods, rains, fires, crop failures, wars, and epidemics by heeding the meadow vole and other population models of scientists such as Dr. Chitty.

We do have Torah to show us how to navigate difficult times when they arrive, and how to respect each other, including those among us who are differently abled or are strangers.

With regard to this week’s Parasha Beha’alotcha: let us hear the complaints about the lack of fish, the cucumbers, the melons, the leeks, the onions, and the garlic; but be more like Moses, and remind one another of the big picture and value of the whole congregation of humans – follies and all.

We are beings favoured with Divine wisdom and sacred books such as the Torah, who can learn from, and find a way through, our dilemmas with the natural world and amongst ourselves.