-

Pausing of the Waters

The building I live in has a water problem. I moved in two years ago, and at the time saw how efficiently the staff and maintenance people attended to a leak in the ceiling in the lobby. Their work ethic and commitment to keeping the building operating impressed me, and also the attentive manner with which the manager engaged with residents coming into her office also felt reassuring.

Meanwhile, I signed the lease and moved in. Leaks continued to plague the building, springing from ceilings, running down walls, and causing them to have to open up the wall behind the sink and toilet of my newly renovated bathroom – twice. This was alarming to me, my nicely plastered walls were now a bit lumpy-bumpy the charm of the upgraded apartment was dissolving into concern about what might come next with regard to repairs.

Our water was shut off time and again, now to stop a burst pipe in the apartments upstairs, and again to stop a catastrophic flood in the sub-basement parking garage, and again to replace the boilers. The building is over 60 years old, and has the ambience and look of a nicely appointed Old World style hotel, with statues and figurines and chandeliers and fountains leaping in the lobby. But, eventually, even with the greatest attentiveness and care, things wear out.

Long time residents tell me that the leaks and water problems have been going on for years, my estimate from averaging the varying time frames they report, about maybe 4 years now. The building has so many nice features, because it is old. The walls between apartments are thick and so it is quiet with little disturbance from neighbours; it is very low tech with no electrified walls or wiring beyond fire safety alarm codes; everyone has a spacious balcony; and as mentioned, the staff have an old fashioned commitment to attending to residents’ needs.

Yesterday, I came home from some errands to find that the water was shut off without notice for an emergency: the city is replacing the drainage system, which apparently has been the cause of all the water backups and pressure leaks inside the building. But, the city broke something and our water was shut off – again, and for an indeterminate amount of time.

Oy! it’s right before Shabbat, and right before Passover, and most of the residents of this building, like me, are Jewish and rushing around trying to get their apartments ready for festive meals and guests.

I was heading out for a Tai Chi class (at the Renge Dojo in Toronto), and got into the elevator. It was crowded with people going out for Shabbat and stopped on a couple of floors on the way down. I made a joke about how boring our building would be if we didn’t have these water shutoffs from time to time. Everyone chuckled and one gentleman laughed, and smiling at me, said he liked making a joke about it instead of a complaint

The truth is, though, they may never end. The other truth is, that we were all in the same boat (or elevator) and instead of staring at the doors or the floor counter on the wall, we were chatting and bonding with our complaint, and also having a laugh together.

Although our ride down to the lobby was brief, it changed something for us all. No longer stuck together in an elevator or in a leaky building, we got to know our neighbours a bit better, and got to step into a new way of looking at our situation, replacing angst and irritation with irony and humour.

Perhaps at this season of turnover, when it is traditional for Jews to read the passages in Torah about the exodus from Egypt, or Mitzrayim – the narrow place, we can find a new way of seeing challenges or barriers to our wellbeing. Part of leaving Egypt meant the Hebrews had to face the barrier of the Sea of Reeds (or Red Sea). Did they stand at the shore and complain? Some of them did! But then, one person, whose name in midrash is Nahshon, saw a way forward, and he put his foot into the water, and the waters withdrew.

Think about some narrow place you may be in, and how you react to that. And then, think about this man who stepped into the Reed Sea first and made a path for others, or even how my joke in the elevator brought change for some residents. Opening up to as many options as are available can liberate us from seemingly endless or hopeless bondage.

Have you tried this lately? write to me and tell me your story, too!

Wishing You a Peaceful Transition in this Season of Freedom Celebration.

-

Full Eclipse

Today, I was fortunate to be living adjacent to the zone of full solar eclipse that passed through North America.

To be honest, I hadn’t made any plans for watching it until the last minute, despite the near deluge of information in almost all the media that crosses my inbox. Since sustaining a concussion at the end of last November, it has been imperative for me to triage all new activities, prioritizing them by need. Everything else then is put into a queue, and if any become obsolete, they are then deleted.

I liked the idea of watching the eclipse, and recalled friends who, in 2017, dashed north to Oregon to watch a solar eclipse there. Some of them also attached a great deal of cosmic significance to the event. This latter part caused me to move the eclipse lower on my to-do list: I’m too much of a pragmatic scientist and grounded intuitive to attach human interpretations to a natural event.

What did catch my interest was an invitation from the Toronto Zoo to the general public to come watch the behaviours of the zoo animals during the eclipse, for research purposes. There is a dearth of data on how different exotic species might change their habits during a full solar eclipse, and as a former zoologist myself, this was an added-on value for acquiring some funky solar eclipse glasses.

I drove to the zoo. As soon as my car merged onto the freeway, I saw flashing emergency vehicle lights on the other side. There was a huge pile up of cars going the other direction. It was only 11am, and the eclipse wasn’t going to start in Toronto until half-past 2pm. Panic was already setting in.

Along the way, overhead information beacons warned of a solar eclipse on 8 April, and to ‘Plan Ahead’. Actually, I had planned ahead, and bought my admission and parking tickets online, fearing that I would make the long schlepp to the zoo only to find no parking and the gates closed due to the thronging crowds filling the park to capacity.

But, I easily found a parking spot and strolled up to the entrance. I noticed a lot of people, mostly those with small children in wagons and adults in wheelchairs, exiting the park. It was only 11:45am.

I ran up to the table where eclipse glasses were being given away. Bling! I was a free agent now, able to watch anywhere and in any way I wanted to. I picked a pair with tiger stripes, for full zoo effect.

My plan had been to show up, have a snack of zoo junk food, and then stroll around. Unfortunately, that wasn’t possible. The zoo was re-developing the large area adjacent to the entrance and food concessions. Mega-loud generators gunned and ground a sonic wave of nausea right through my vulnerable brain and nervous system. I immediately lost the ability to finish a thought, but did know to duck into a large building to get away from the cacophony and decide what to do. It was not possible for me to stay in the park unless I could get far from this noise. Of course, no one else seemed to notice it at all: loud as it was, everyone else seemed to just ignore it.

I know, however, that their brains and bodies were hard at work blocking out the noise, coping with the stress and energy drain that it caused, and producing escalating irritability for seemingly ‘no reason’. I left the building and made a beeline to the far end of the zoo, hoping to evade the noise. This was tiring. There, all the food concessions were closed for the season. No food. And, there was more construction, in the form of jackhammers on cement.

I began to wonder how the zoo was going to separate the behaviours of its animals resulting from the solar eclipse with those caused by the effects of all that construction noise. Was anyone going to factor that into the data analysis?

Well, since no asked me, and I was starting to feel a bit like a Larry David, irked by this obvious oversight in the research promotion, I decided to leave. My balcony at home, I realized, was facing exactly the right direction to see the full eclipse, and I could have all the snacks I wanted: and, bonus – observe animal behaviour, of my cats, during the eclipse.

I still had plenty of time to get back home, it was only 1:30pm. Recalling the traffic pile-up scene on the freeway heading there, I took the side streets back. Surely, the panic on the freeways would have escalated exponentially by now, only minutes from the start of the solar event.

I got back home, wiped down my patio table and chairs, and sat with a lovely coca-cola on ice, my iPhone’s camera ready, and watched the whole event.

It was a cloudy day, the sky was overcast. Looking down, I saw that traffic was lighter than usual, but also that there was almost no one out on their balconies, as I was, or paying much attention. Perhaps they thought that, due to the cloud cover, there was nothing to see.

© Susan J Katz 2024 I sat patiently, anyway, knowing that small breaks of sky or thinner regions of cloud would reveal the sun, in its waning and waxing. And, sure enough, it did. I was so excited every time the river of clouds overhead thinned just enough to show some sun, like a Can Can dancer flipping her skirts up just enough to get a glimpse, and then keeping you at the ready for the next moment of revelation.

Meanwhile, down on the street, no one cared.

I’d had trouble understanding the apathetic or amused responses from several people when gaily told of my plans to watch the event. “I’ll watch it on TV”, they’d said: even people living right here in the path of eclipse. Maybe having the cloud cover instead of a fiercely bright sunny day felt like just another disappointment, another event that was ill-conceived or poorly staged, another gadget that didn’t work as advertised, or broke. They turned to the virtual version of the event, instead of the analog natural event going on right outside their doors.

Somehow, our electronic screens have replaced great and awesome natural events. The next such event will be here will be in 2144. I suppose an AI version could be created now, and save everyone from not being around for a sunnier day, 120 years into the future.

It is the disconnect from our natural environment that troubles me so. Yes, this is urban Toronto. Does that mean that only manufactured, ersatz natural events are real? With this realization, I now better understand how our modern disregard for the importance of things non-human has come about.

We debate publicly as to whether climate change is man-made or not. But, has anyone paid attention to what in their own backyard is also at stake? birdwatching has evolved into telephoto-lensed camera-lugging, to snap the most professional picture of a birds. Learning bird calls and silhouettes, and patiently watching for characteristic behaviours, has replaced by looking into a viewfinder or a smartphone screen. Outdoor appreciation activities have given way to beyond-ultimate skiing, ultimate mountain biking, ultimate rock climbing, complete with selfies or video recording.

Can anyone just ‘be’ in nature any more?

I took a few photo mementoes, between squeals of delight at seeing the crescent sun pop in and out of breaks in the clouds, from my balcony. The next opportunity would be 120 years from now.

© Susan J Katz 2024 By the way, my cats joined me for a while, bravely climbing onto my lap to peek over the balcony railings before decamping to their favourite spots on my bed.

As soon as the eclipse ended, just before 4:30pm, the clouds finished passing by and the sun came out, full and bright.

-

The Art of Saying ‘No’

If you have visited my website recently, you probably noticed that it has been under construction, and either the posts are hidden, or the whole website was down for maintenance.

That was intentional, and for a good purpose. I had begun noticing how so much of my time was spent taking care of other peoples’ or organizations’ needs. Meanwhile, my true desires, to provide spiritual care and intuitive-guided counselling and have my own oboe studio, were sent to a lower berth of engagement.

In the autumn, these choices to serve away from my desires and purpose, came to the forefront of my attention. Ready to change gears and re-evaluate my choices, things began to drop into place. Being a highly sensitive/highly intelligent person, with particularly strong gifts of intuition and insight, I found a practitioner with similar traits and life experiences with whom to explore how I was attracting other peoples’ projects and not attending to my own.

Just as we began this work, though, I was struck by a hit-and-run driver while walking in a crosswalk next to my home. The resulting spin around from the impact caused me to have a concussion. I was left simply unable to do anyone’s work, mine or others’. I decided to keep working with my career transition coach anyway, alongside the medical care I needed to recover.

Here was an opportunity for change. My focus and attention were now expanded beyond my normal and long-held boundaries and patterns. Some things jumped out at me as being keys to my transition away from what other people do or want, to defining what I want. One of these items was an essay in the New York Times by a guest writer, about her ‘Notebook of Noes’1

So began my reconstruction, or resurrection, of what my intentions were when I became an independent, freelance spiritual care counsellor, writer, and musician.

No sooner had I engaged the services of my coach, when emails and calls started to come in, from people wanting my services. It was actually astounding to me, having found myself pretty much ignored for a very long stretch, but not knowing why. My coach and I had no explanation for this opening of the heavens and ringing of phone and email contacts. My becoming available was being sensed out there, some semiophoric pheromone or energy cloud was wafting through the ether, with a big empty channel leading toward my phone and email and ultimately, to me.

Was I going to fill up this beautiful new space I had cleared out for myself, with others’ projects? With a lifelong history as a woman, and one who accommodates others for all sorts of personal historic reasons, I now had clarity about my own system for subsuming my needs underneath those of others’. Was it for praise? extra credit and good grades? fear of rejection or being fired from a job? Here is the spot where you can plug in your experience with this sort of relinquishing your goals to serve others’.

It is one thing to identify this sort of dynamic: it is another thing to change that pattern.

Starting with being mindful of my goals and how much I was now moving ahead in establishing their fulfillment, I could then ask myself, “Is this offer/request in alignment with my agenda and purpose, or will it take up time that I have now set aside to write/make music/set up counselling?”

In the past, it would have been very hard for me to see the difference, but with a bump on the head and a list of Noes, I have the impetus and tools to choose the requests that fit, and politely say ‘No’ to the others.

Enjoy my new website and its features. If you are looking for Spiritual Care Counselling, Intuitive energetic self-management, or music performance, please don’t hesitate to contact me for a free 20 minute consultation.

Wishing You the Best of Health and Personal Growth…Susan

- ‘The Mind-Boggling Simplicity of Learning to Say ‘No’ by Leslie Jamison ↩︎

-

Please Note…

~Please Note: the Blog Page is being revised and all 70 posts will once again be available for viewing soon!

-

A Reed for the New Year

The Jewish New Year holiday of Rosh HaShana begins this evening at sunset. It is an auspicious time of reflection on the past year and what went well, and even more importantly, what did not. We are encouraged, through our traditions and liturgies, to go even further; and examine the things we ourselves did that perhaps made things not go well for not only for ourselves, but for others.

As time moves on, so do traditions. Communal prayer, which replaced the animal sacrifices of Judaic Temple times, was considered a time to be with others to pray and reflect on our relationships with God, with self, and with others. Full prostration by not only the prayer leaders, but congregants as well year ’round, was not uncommon, such as during the Aleinu prayer. Tears and beating one’s chest over the heart, and other gestures, covering the head in a prayer shawl or scarf, provided solitude, as well.

Things have changed, though. Prayer spaces are crowded during holidays, and priorities as to what we show to others have shifted. Long services often become a time for restless shuffling of nearby congregants, scrolling on mobile phones, thoughts of luncheon meals and guests, as well as tempting redirection away from deeper or painful thoughts towards uplifting songs and instrumental music from the prayer leaders.

Let’s face it: it’s hard to do ‘deep reflection’! A relative used to glibly say, wineglass swaying in her hand, “Why would anyone want to do something hard if they don’t have to?”

Yes, why would they?

I’ve opened this post with the usual, annual, Jewish invitation to ‘reflect deeply’. It’s hard, and where are the instructions! I agree. So here is one way to think about it….

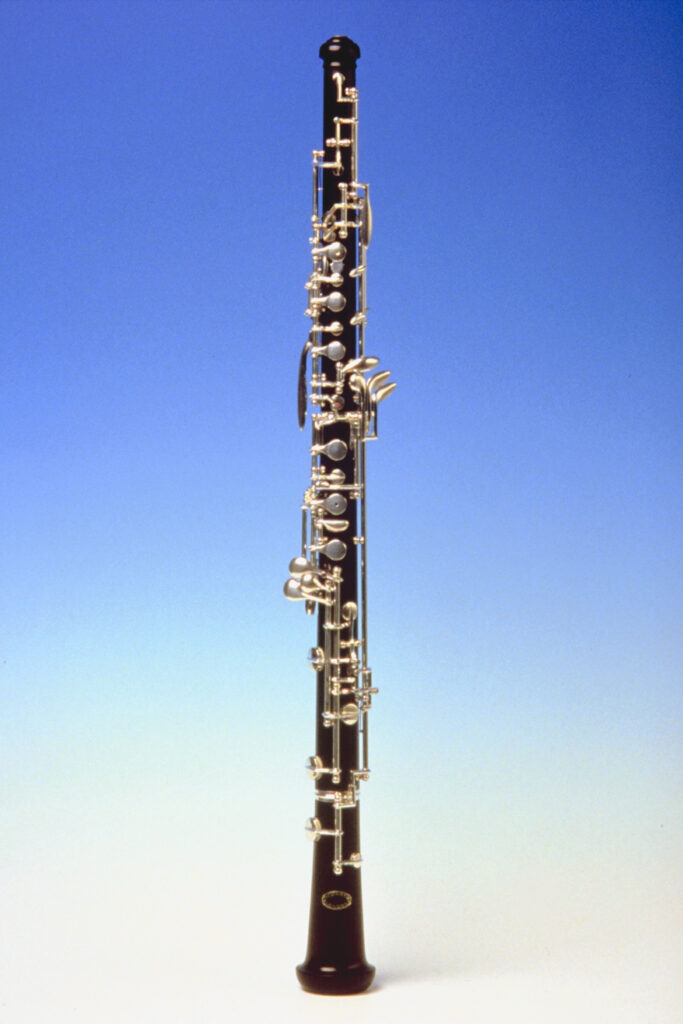

The one thing that defines the personality and angst of being an oboist, far above anything we do or create, is our Oboe Reeds. Finding or making or being gifted the Perfect Oboe Reed is the ultimate quest for an oboist. Why is that?

An oboe, the long wooden conical bore with keys on it, a bell at one end and an opening to blow through at the other, is not the part that makes the gorgeous, plaintive, oboe sound. It is the reed that allows the correct and perfect sound to move through the bore with the correct selection of keys for each note, become amplified into warm, dark, sumptuous sound waves, and gracefully round itself as it resonates through the bell. With an unresponsive reed, one that is too hard to vibrate naturally or too soft to hold its shape under embouchure pressure, the sound is, well, lousy. Quacky, like a duck, which is what beginner oboists are often accused of sounding like.

So, there are a few things going on that an oboist has to control: the quality of the instrument; good habits with regard to embouchure, breath control, and fingering of keys; and using an excellent reed.

It’s not too hard to acquire a good instrument, although they are expensive! I happen to own a wonderful Violetwood oboe that plays like a dream. However: Embouchure, breath, and fingering control are built and maintained by quality instruction in technique, and you guessed it: tons of practising those techniques!

That leaves the bane of all oboists: the reed. It’s really hard to make or buy a perfect oboe reed. Making them requires good tubes of cane, and then gouging them to the right thinness, and then assembling and scraping the blades down, but not too much….You can buy a really good one, but it will still need your expertise to perfect it. The oboist will still need to have a good well-sharpened reed knife to whittle away on it, correctly, testing it at each slight scraping away of the cane until it feels and sounds perfect.

My teachers always emphasized the primary directive of adjusting the reed to the player, and not vice versa. Settling for a bad reed, one that is not responsive, or plays too flat or too sharp, means monkeying around with your breathing, posture, embouchure, fingering, in order to get a decent sound out of it. In other words: the reed is controlling you.

In the process of doing all these contortions, to the point of losing all your hard-earned good technique, you are no longer making your music. You are relinquishing your unique identity and timbre of sound, your signature as a musician, in order to produce instead an adequate sound, from a poorly crafted piece of cane. Your ability to play as a unique and expressive musician and muse of the instrument are the cost of this battle for control of the instrument. Convenience has won out.

Again, back to my wineglass-waving relative. “Why would anyone want to do something hard if they don’t have to?”

Making reeds is hard! Making excellent reeds is even harder! But, as musicians, driving to capture the correct sound for who we each are, it is imperative to strive to make them. Or else, we are lost to a poorer quality sound of convenience.

Just like the oboist, we must patiently and attentively whittle at those rough places. The easier ways out – of letting the reed, or the situation, or that other person, control you – will cost you your self-hood.

I recently received an email advertising a master class in learning how to adapt to and play with low quality reeds. Imagine! The premise is: that bad reeds abound. They come from making them without enough expertise or good materials; or else we buy them, and are unable to finish them well. Either way, this reed hack master class will teach you how to distort and bend your good habits and technique in order to play low quality reeds.

I immediately thought of my teachers, often correcting me for doing just that: trying to get a good sound out of a bad reed, thus sacrificing the hours and hours of hard work I’d done to develop good technique in the process. Those reeds, they said, needed to be either adjusted or replaced.

Looking at this past year now, and the unknowable that will unfold ahead, how will you adjust your reeds? will you adjust yourself further and further to meet the needs of reeds or situations that are unsuitable? or take the opportunity this time of year sets aside and do the satisfying work of refining these situations and yourself, forming lovely reeds for playing your song?

I wish you all a year of good music, for yourself and with others, and all the joy and connections that music brings your way.